If — let’s say today — you and I were to ride into New York City and open the doors at Rikers Island, freeing every person imprisoned in that city’s most notorious jail, what would happen? Chaos? Rioting in the streets?

Consider this, though, before answering that question for yourself. On a daily basis, 78% of the inmates in Rikers Island haven’t been convicted of a crime. Nearly 4 in 5 inmates are in Rikers awaiting trial, unable to afford bail. Of those roughly 7,600 people, 2.2%, about 170 have been charged with murder or rape. An astronomically higher number — almost 3,700, roughly half of those pretrial detainees — are awaiting their day in court for misdemeanors or drugs.

And, to tie that back to the racist nature of policing and prisons in both New York City and the United States as a whole, 52% of those imprisoned in Rikers are Black. 35% are Hispanic. 90%, in total, are people of color. (All of these numbers, to verify, can be found in this 2017 report from the NY Budget Office, and further discussed in this Village Voice article.)

So… what would happen if we opened Rikers today, and let everyone there go free? Chaos in the streets? Or would the vast majority of its detainees go back to homes and families that, if we’re being honest, they should have been able to return to in the first place?

I ask because Marvel’s Spider-Man, released in 2018 by Insomniac Games for the PS4, has its own answer to that question. And it ties into a host of larger questions about policing, superhero fiction, and the existence of America’s carceral state.

***

[Spoilers for the main game (but not the DLC) of Marvel’s Spider-Man follow.]

One of the first things you, the player, help Peter Parker do at the start of Spider-Man is break up a drug bust. After defeating the Kingpin, Wilson Fisk, in the game’s opening moments, New York City is besieged by a whole host of petty criminals. And over the course of the game’s 25 or so hour storyline, that crime never peters out — it just exists, ostensibly to fill the vacuum left by the imprisonment of NYC’s most notorious mob boss, but in reality without any kind of grounding or motivation. It exists, in other words, so that Spider-Man can be a video game.

And don’t get me wrong — in many aspects besides its disfigured understanding of policing and prisons in the city it calls home, Spider-Man is a truly excellent video game. Its version of webslinging is some of the most satisfying movement I’ve ever experienced on any platform or controller — fluid and fast, with exactly the right balance of precision and imprecision. It leads to a perfect flow-state, as Spidey zips in and out of various landmarks and crime scenes and research stations (all some of the optional open-world objectives this game offers for the player to explore), creating moments of ephemeral zen. Its combat system is detailed but not overwhleming, and, by and large, the boss fights it offers with a surprisingly wide array of Spider-Man’s most famous adversaries are excellently designed. The penultimate encounter with Mr. Negative (aka twisted father figure Martin Li) is particularly memorable for its near-perfect flow, difficulty, and arena design. At moments, if not for the 3D action and big budget engine, I could have sworn I was playing Dead Cells — and there’s no higher praise I can give for movement and combat than that.

But — and this is the crux of every issue, both small and glaring, that this game exhibits — Spider-Man just can’t help itself from being a video game. In some of the less memorable boss fights, this manifests as a series of blink-and-you’ll-miss-it button prompts that are simultaneously abrupt enough to destroy the game’s flow and last long enough to rip apart the illusion of quick, reactive superhero action. And in as much as every element of this game is an illusion, very little interrupts that illusion as effectively as its love-affair with quick-time events. When that Dead Cells illusion broke and Spider-Man morphed into a Quantic Dream game (the likes of Heavy Rain or Detroit: Become Human), the contrast was vast and jarring. Thankfully, those moments were relatively rare.

What isn’t rare in Spider-Man though is its acute case of checklist syndrome, or the open-world bloat that affects it far worse than most comparable open-world games. At four separate points, alongside some kind of shift or movement in scope, the game positively disgorges a bunch of icons and markers out onto its worldmap for Spidey to find and collect. At first, these are just things to zip to, pick up, and zip away — and those I more or less enjoyed for what they were. The fun of dropping out of a long, arcing swing to snap a picture of a New York City landmark unleashes the same satisfying dopamine release as loosing a perfect arrow in Breath of the Wild or Horizon Zero Dawn. Peter Parker’s camera even has its own version of bullet time (a concept I’ll leave alone here for want of time, but would be worthwhile picking up in conjunction with Susan Sontag’s work on the implicit violence of photography).

But soon after I’d checked off the backpacks and landmarks, the game began dropping more and more complex objectives out into its world. And while the research stations and taskmaster challenges are more of the same video gamey filler I’ve come to expect from similar projects like Sony’s God of War, this stream of checklists and objectives eventually circled back around to its inception — to the nature of crime in a superhero narrative, to prisons and the commodification of human bodies, and to the game’s inability to imagine something outside the bounds of a video game.

***

To fully illustrate the extent of what Spider-Man does badly, I should first go into what it does well. And In a word, its relationships. The writers at Insomniac clearly understand how to write superhero stories, and their work on Peter Parker and both his friends and enemies is some of the best in any recent comic adaptations. The depth of character given to both allies like MJ and Miles Morales and villains like Otto Octavius and Martin Li are far beyond anything the Marvel Cinematic Universe managed to achieve (in, oddly enough, a shorter, more focused package), that they nearly reach the transcendant heights of Into the Spider-Verse. Peter’s relationship with MJ feels realized, authentic, and moving. And while I wasn’t the biggest fan of the early MJ stealth sequences, once she gained some ways to manipulate the environment and enemies around her (first with lures and then, eventually, with a taser), they started to feel more in line with the game’s larger, engaging, and almost XCOM-like approach to stealth. Through all that, the game’s writers managed to avoid one of the genre’s surest pitfalls — passive love interests existing for the gratification of the central hero. “Love interest” barely feels like an adequate way to present MJ’s role in this game; the word she and Peter use, “partner,” is much closer to the truth. That might be Spider-Man‘s greatest success.

Though, as with any strong superhero story, the villains must shine too… and they do. I already mentioned Martin Li and Otto Octavius; for Li, the main villain for about two thirds of the game’s length, Insomniac managed to marry environmental storytelling and some excellent cutscenes to make his motivations and history clear. And when the game finally reveals what happened to him as a child — the source of his quest for vengeance — it injects the subsequent boss fight with a strong dose of pathos.

The same goes for Octavius, who begins the game as Peter’s employer and mentor and ends trying to throw him off the roof of Oscorp Tower. Doc Ock is an origin story done right (and thankfully, this game avoided the tired trope that Spidey’s own origin story has become) — one where we slowly see his history and motivations coalesce into a horrible, self-destructive package. Truly, Spider-Man is at its best when it becomes a game about Peter Parker and his relationships — to the people he cares about, both heroes, villains, and warped parental figures that drift in between. The reveal of the Sinister Six (though never quite named that in-game) remains one of the best cutscenes I’ve ever seen my PS4 put out, and — as the game’s climax pays off twenty hours of buildup and tension — even in its melodrama feels wholly earned. If that had been all this game was — twelve hours instead of twenty-five, about relationships and revenge and trauma, I’d be over the moon.

But, sadly, it’s not. And to understand why, we have to go back to Rikers Island.

***

To close out Spider-Man’s second act, with all of Spidey’s nemeses locked up in a fictional supermax called The Raft, Octavius stages a breakout at Rikers. (And yes, the game spells it Rykers — in either case, it’s still the same island.) Peter flies in on a helicopter with his police contact, Captain Yuri Watanabe, to find literal hordes of inmates wielding rocket launchers and riot shields, terrorizing guards and forcing their way out towards New York City.

First, let’s talk about the weaponry on display here — and go back to the root of Spider-Man‘s problems: its inability to think outside the bounds of a typical video game. Because this isn’t the first time we’ve seen rocket launchers and riot shields; every class of enemy in the game, from Fisk’s mobsters to Mr. Negative’s Demon gang to the PMC soliders we’ll soon encounter (and discuss), carries the same weaponry and behaves in more or less the same manner. This, of course, leads to consistency throughout Spider-Man‘s combat encounters — it allows the game’s combat system to unfolds in an expected, linear manner, as it would in a game like God of War.

Except, in God of War, Kratos spends his days fighting a cadre of angels, demons, and creatures that exist somewhere in between. Here, Spider-Man drop-kicks and electrifies people who — as we established earier — are by and large providing free labor to the prison-industrial complex while imprisoned on misdemeanors and drug charges. Of course that’s not apparent in the game’s version of Rikers, but it raises a larger problem with the way Spider-Man approaches crime. As I mentioned at the start of all this, crime primarily exists in Spider-Man as staging for its brand of open-world video game. The petty criminals that pop up throughout New York City have no motivations — and with that, none of the nuanced characterization that far larger villains like Octavius and Li receive throughout the game’s story. Criminals, in the world of Spider-Man, exist because they exist. They will always exist. And we will always need police (and a masked superhero) to combat their existence.

In the real world, crime is driven by access to resources — the inability to receive and maintain basic necessities. In other words, people shoplift when they can’t afford food; just ask Jean Valjean.

Les Misérables may actually provide a useful piece of contast here as well — after all, it presents vision of policing and prisons in polar opposition to Spider-Man‘s permanent state of crime. Javert, the novel’s iconic antagonist, can never see beyond his obsession with law and order, and crystallizes his fixation by repeating ad nauseum the mantra that men like both himself and Valjean can never change. Just listen to “The Confrontation,” where he recites Valjean’s prisoner ID number over and over again, supplanting his name, marking him as less than human.

In a much more implict and roundabout way, Spider-Man agrees with Javert — at least about the core nature of crime. Criminals just… exist, in this vision of New York. “Every man is born in sin,” as the Inspector sings; in other words, outside of the musical’s heavy religious imagery, bad people are just bad people. They will always be, and as such, they will always need the police to stop them.

***

Two years ago, when this game was released, I’m not sure many outside the small cadre of Marxists would have taken this kind of analysis seriously. In our present moment though, as videos and accounts of police brutality towards Black people continue to pile up across the United States, I think it’s pretty difficult to deny the core problems with how Spider-Man portrays criminals and crime. Moreover, it should be even harder to reconcile it’s strangest elements — the divergent way the game depicts the NYPD, a police department larger and better equipped than many of the world’s militaries, and Sable International, a private military company that joins the escaped prisoners, Demons, and petty criminals in antgonizing NYC’s streets in the final third of the game.

Sable International, in 90% of its appearances in Spider-Man, is depicted and labeled as outrightly fascist. Literally — Peter himself throws the word out there as he power-kicks their guards and officers into the stratosphere. But beyond that initial similarity to the true face of American policing we’ve seen over the past month, they also move in to stem the flow of a deadly respiratory pandemic — yes, a pandemic — that Octavius unleashes just after the Rikers and Raft breakouts. To do so, they set up literal internment camps throughout New York City, imprisoning citizens for whatever reason they want (which, as the game usually makes explicit, either for protesting their violent occupation or for no reason at all).

These, of course, are then added to the game’s world map as more checklist items. And with that comes the game’s strangest contradiction of all — beating and imprisoning petty criminals, a category the game literally labels “Thug Crimes,” rests on a list just below the liberation of political prisoners. The implication, of course, is that while the police are good and prisons necessary, privatized versions of those institutions are dangerous and oppressive… because they might imprison people who don’t immediately deserve it. There is no hint of their similarities, or any conception that the police themselves may only be a shade removed from the crimes Sable International commits against the people of New York, because Spider-Man at no point acknowledges that the criminal justice system might itself be unjust and broken. Case and point: on multiple occasion, Peter vocally wishes that the Sable mercenaries would go take care of “real criminals” instead of fighting him — sometimes moments after clearing their literal internment camps! The people he frees from those camps, incidentally, go on to file police reports so that the NYPD can once again supplant one occupying army with another. Through all these venues and avenues, Spider-Man can’t help itself but be a Video Game — gamifying both crime and a disconnected idea of liberation in ways that strip both of any larger context and meaning and transform them into items on a checklist, there for a superhero to endlessly solve and replay.

***

I’m sure some readers might make it to this point and protest that my analysis seems to boil down to “Spider-Man is a video game.” After all, video games have enemies — often faceless goons who exist to be a main character’s punching bag. Here, prisoners and criminals fill that role, and maybe we shouldn’t think too deeply about who those enemies are or what their presence means. It’s just a video game.

But that’s bullshit. We’re long-established in a moment where video games, from God of War’s single-shot gimmick to The Last of Us Part II‘s attempt at a cinematic revenge tale, have begged in increasingly exorbitant ways to be recognized as art (long after most reasonable people recognized them as such). And being taken as art necessarily comes with a kind of criticism that some in gaming fandom bristle at. But denying that reveals a fundamental misunderstanding of what art is and means — in essence, that it merits criticism. A work that tries to say something larger about the world, about people and relationships and the systems that manage our existence, deserves to be called on its bullshit when it fucks up. And while Spider-Man gets some things affectingly right, it also has a massive, all-encompassing blind spot when it comes to criminalization and the nature of crime.

In particular, when it comes to enemies, the choice of which goons to mercilessly pummel in a given game isn’t some offhand, random choice that comes to developers in a dream. Valve, in the original Half-Life, deliberately created a story about government cover-ups by filling that game’s levels with scores of US soldiers and troops. And, in Half-Life 2, a game squarely about assimilation into a fascist state, reveals that a subset of the aliens fought both by Gordon Freeman and those soldiers were in fact enslaved and mind-controlled. Those games, respectively released 20 and 14 years before Spider-Man started gracing shelves, should serve as easy evidence for the relevance of enemy choice on themes and stories — just as much as all the late-2000s Call of Duty and Medal of Honor entries about slaughtering scores of nameless Middle-Easterners in the name of American patriotism. Those military shooters had a reckoning moment with Spec Ops: The Line (at least, in the sense that some in the gaming world seemed to develop some self-awareness) — will superhero fiction?

Superhero comics, as it is, are usually a far more complex medium than their adaptations let on. (One important exception might be HBO’s Watchmen — a miniseries even more relevant to our current moment than any of these video games.) But as with Spider-Man, comics are typically at their best when their focus narrows and becomes more intimate — when writers focus on characters and their relationships, and on the idea that these are real people behind their costumes and masks. At its best, that’s exactly what Spider-Man does; it feels like a comic book not just in its action, movement, and sound design, but in the way it approaches its heroes and villains.

It’s just a shame that, in the end, it also insisted on being so unfailingly, unflinchingly, a Video Game.

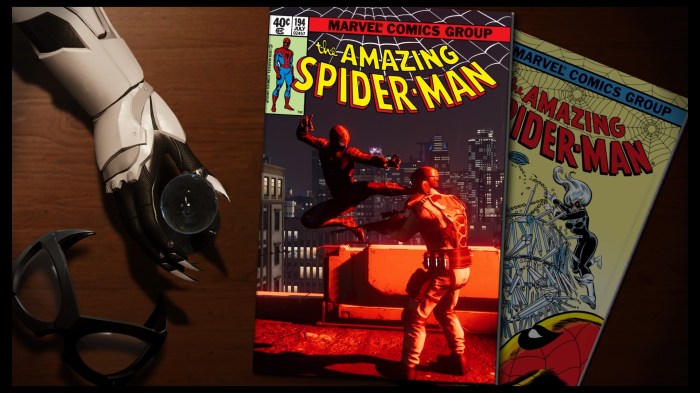

Gorgeous 🙂 I want to make love to the use of background and iconography!

LikeLike

Nice use of fuschia in this shot.

LikeLike

Looks gorgeous and sublime dude

LikeLike