As 2020 ends, I’ll be dropping posts about video games I played and replayed this year — the ones that most effectively summed up this strange, chaotic trip around the sun. The posts are in no particular order, and can be read in whatever sequence you desire. Fair warning: this post contains spoilers for a game called Deus Ex.

Deus Ex begins, as any game about the decay of the neoliberal world order should, with a terrorist attack on the United States. It’s 2052, and a paramilitary constitutionalist force called the NSF is directing a plot from inside the Statue of Liberty. JC Denton, agent of the United Nations Anti-Terrorist Coalition and the game’s perennially sunglass’d protagonist (don’t forget: his vision is augmented), is dispatched to Liberty Island to take out the terrorists’ leader. From the South Dock where that mission begins, the skyline of New York City rises in the distance, glowing and distinctive in the darkened night. It rises — as, of course, it should — without the World Trade Center. The game explains that the buildings were destroyed in a terrorist attack, much like the one you, Mr. Denton, are trying to prevent. Perfectly historical, right?

Deus Ex was released on June 13, 2000, without the Twin Towers in its skyline.

The truth about that piece of trivia, revealed by the game’s development team at Ion Storm, was that the game’s engine didn’t have enough memory to keep the WTC in that skyline. As an explanation, they wrote in a past terrorist attack: fitting in an apocalyptic world wracked by militant violence. By itself, it’s just eerie — the kind of eerie that evokes incredulous looks and a short laugh.

But when the game around it proved so prescient about the future, it becomes something more than that: one of video games’ enduring legends. Deus Ex predicted 9/11.

***

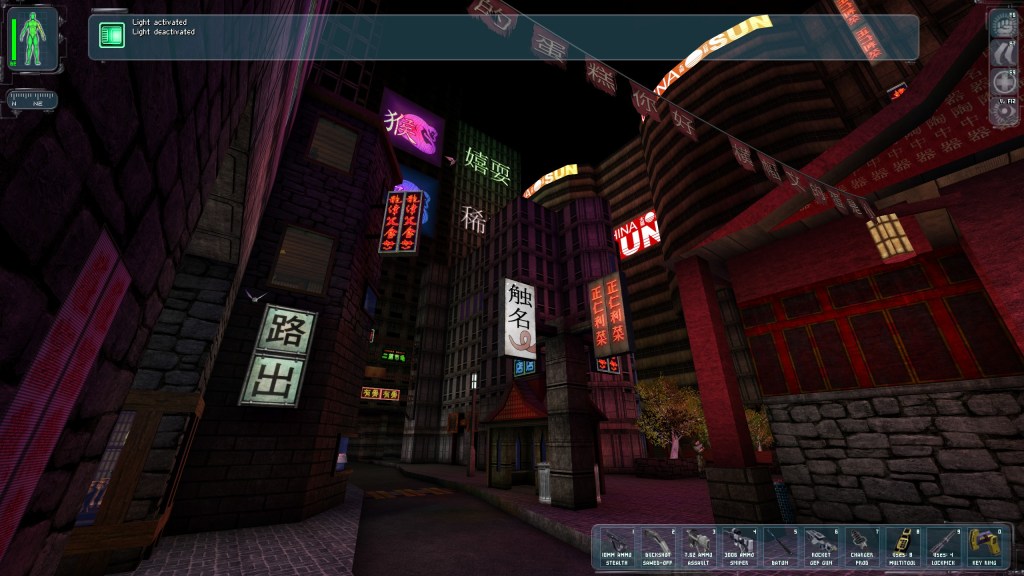

In hindsight — though the decades since its release have granted games enough memory to not only hold New York’s skyline, but to recreate the city itself — Deus Ex remains a pivotal text for 21st century games. It spawned an entire genre of “immersive sims” — including games like Dishonored, Prey, and BioShock, among others — and beyond that, spread its influence as far as Breath of the Wild and Gone Home. The end of 2020 has seen the (unqualifiably brutal) release of Cyberpunk 2077 — a game billed as an “open world” riff on Deus Ex‘s foundational piece of video gaming cyberpunk. To play the game in 2020 is to open a time capsule, and to see two decades of gaming history spill out in the most unexpected ways. That, in and of itself, deserves revisitation.

And yet, Deus Ex‘s historical significance alone didn’t impel the fresh playthrough I gave it in 2020, nor vault it onto my Game of the Year list; instead, it was the sheer eerieness with which it seemed to predict our current moment: the forces governing it and the currents swirling beneath its surface. Not as a piece of trivia like a missing building in a skyline, but as blazing neon sign that screams: NONE OF THIS WAS UNPREDICTABLE.

YOU JUST WEREN’T LOOKING HARD ENOUGH

For all its complexity, summing up Deus Ex in a single word is simple: conspiracies. The game’s plot features a series of nested conspiracies, all run through one central, iconic switchboard: the Illuminati. By way of government organizations and private industry, the Illuminati pulls the world’s strings from the shadows, directing the future by influencing the present. And the present — of 2052 and, as it turns out, 2020 — features a deadly respiratory virus sowing fear and death across the globe.

The similarities between Deus Ex‘s pandemic and our own are not universal — at least, not in their origins. Contra to our own conspiracies, COVID-19 wasn’t created in a lab. 2052’s “Grey Death,” as is revealed in the game’s third act, was manufactured and released by Bob Page, a billionaire industrialist and Illuminati leader, to force the world further beneath his boot: after all, his company was the one manufacturing its vaccine, and his pocket agencies — like FEMA and UNATCO — were there to decide where it would be spread.

But, in 2020, we’ve seen the same dynamics play out. Countries brought to the verge of collapse as governments and government officials deciding to whom and to where resources should be delivered. Politicians and strategists sabotaging their own populaces for electoral gain. Bizarre, homegrown conspiracies about viruses and vaccines and miracle treatments and cures emerging every week like fungi from the woodwork. Deus Ex‘s most basic tenet is one of the loss of truth — or, at least, its impossibility in a world crumbling beneath the weight of conspiracies. At its core, it’s a game about ideology, and a world in which ideology has deftly filled the gaps left behind by truth’s departure.

And while Deus Ex is fond of globetrotting — with extensive sequences set in Hong Kong and Paris — its thematic weight and the ideology it sets out to critique are, at their core, distinctly American. It takes us to the natural endpoint of capitalism: of government not only placed in service of billionaires and corporations, but parasitized by them until nothing of its original function remained. As Denton follows all those nested conspiracies back, he moves from investigating UNATCO to sneaking through the labs of VersaLife: a company fishing in the well of transhumanism while creating their own “transgenic” species of animals. VersaLife leads him back to Bob Page — an uncanny combination of Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk written just as both began to accumulate inhumane amounts of wealth. Seen in the rearview, Page Industries seems eerily prescient. Had COVID waited another 30 years to arrive, it’s not hard to imagine Amazon manufacturing its vaccines.

To put everything back in focus, Deus Ex presents a vision of a future America eerily like our own — wracked by a pandemic manipulated by industrialists, corporations, and politicians for their own personal gains. People starving in the streets and dying untreated in clinics as the wealthy disappear to secret hideaways or receive experimental treatments. In the game’s own history, a terrorist attack on a New York landmark — the Statue of Liberty — spurred the US government to strengthen its surveillance state. That reality came to pass less than 18 months after the game’s release in 2000. To play Deus Ex in 2020 is to see our own world refracted through a strange, distorted, yet uncannily prescient lens. It’s to understand with creeping dread that this world we’ve found ourselves in was never unpredictable; it was coming all along.

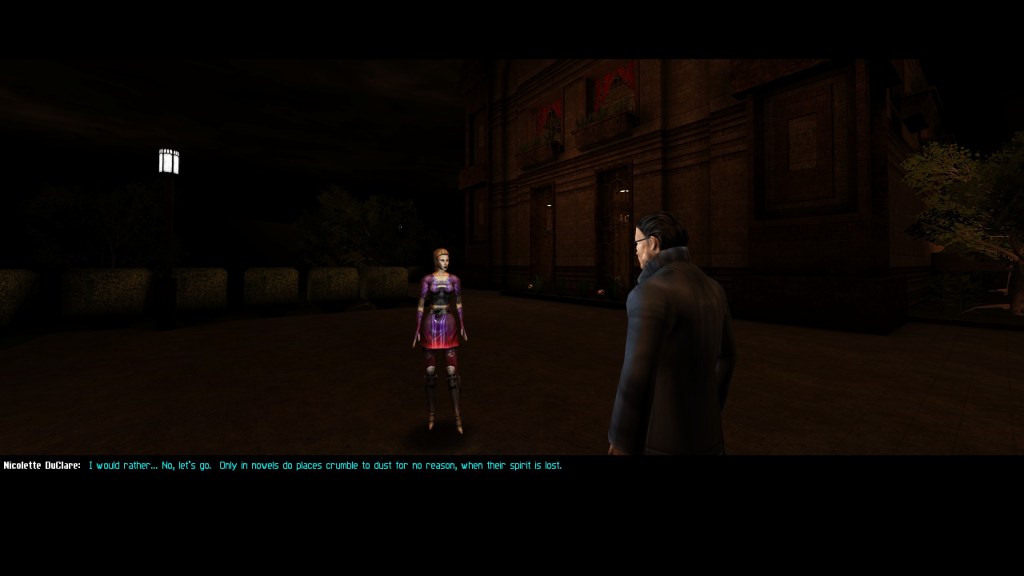

At its conclusion, Deus Ex forces JC Denton to choose. With control of a global communications network at his fingertips, he has three possible options: consign the world to late capitalism via the Illuminati’s unbreakable control; take Bob Page’s place and fuse with an AI, essentially becoming a transhuman god; or nuke it all and send everything back to a pre-technologic age. None of these are good endings — but, as both Deus Ex and its sequel Invisible War remind us, sometimes the world has gone too far for a “good” ending to be possible. At a nebulous moment in the past, a rubicon was crossed. You can’t put the genie back in the bottle, or reassemble the contents of Pandora’s Box. There is no deus ex machina, no god from the machine; you are left with a broken world and no way to fix it: only three, terrible choices. Pick your poison wisely.

Of course, Deus Ex does have a secret fourth ending. A dance party.

If only we could find that cheat code for our own reality.

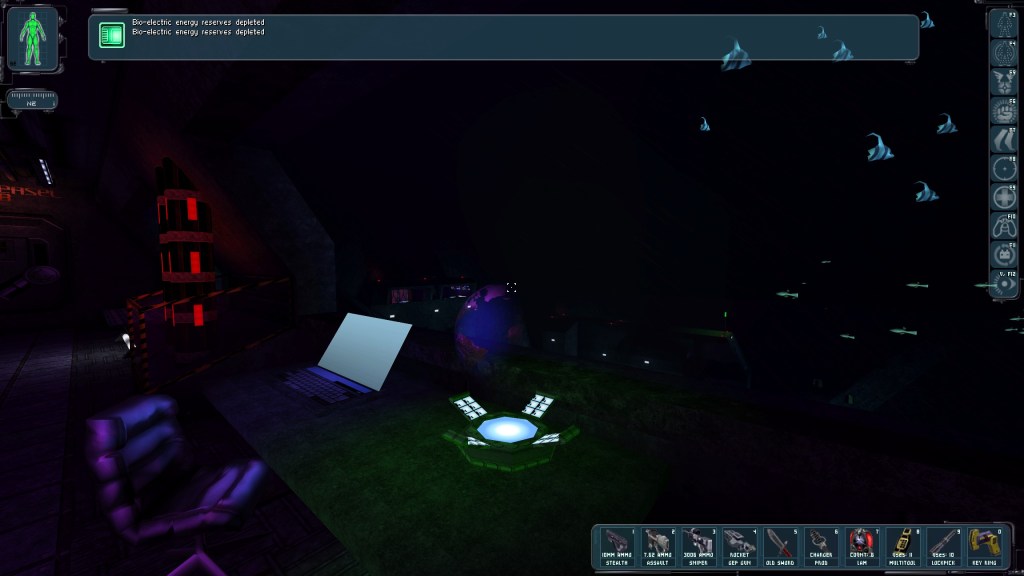

Note: all screenshots are from my playthrough of Deus Ex: Revision — a mod that updated the original game’s graphics and maps. And yes, I never remapped the screenshot key off of JC Denton’s flashlight.