As 2020 ends, I’ll be dropping posts about video games I played and replayed this year — the ones that most effectively summed up this strange, chaotic trip around the sun. The posts are in no particular order, and can be read in whatever sequence you desire. This piece contains spoilers for Death Stranding and the final season of The Good Place. (…and Animal Crossing, I suppose, though I don’t know what a spoiler in that game would really be.)

In most respects, Death Stranding and Animal Crossing: New Horizons couldn’t be more different. One features a colorful, tropical island free of all conflict and division: a weird, wacky paradise of the kind our world could never provide. The other quite literally envisions a future of ruin — in which lingering ghosts double as nuclear warheads and roving marauders attack the couriers tasked with keeping human connection, and thus the world, alive. And yet they have three distinct things in common.

First, they are both irrepressibly singular. Hard as you look, there’s nothing out there quite like them.

Second, they both deploy a kind of collaborative multiplayer in service of themes of friendship and interconnection.

And third, both are fundamentally — at their core — games about work.

Nearly five years ago, a few months after I created this site, I wrote a piece about a game called Firewatch. At that point in early 2016, I was still growing into my awareness of games as a medium — I had never owned a console beyond a Nintendo handheld, and played most of what I played on my college laptop. And Firewatch captured my imagination in a way that very few games ever had; it was something I hadn’t experienced before. It was a “walking simulator” — a formerly perjorative term that has since grown into its own genre identifier — or a game in which the main mechanic was movement and navigation through a linear, pre-determined world. Dear Esther, Gone Home, and Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture preceded it, among others, but Firewatch had developed their ideas outward by adding the kind of branching dialogue typically found in visual novels. Walking, as it turns out, wasn’t really what those games were trying to simulate.

Death Stranding, on the other hand, is — in fact — a walking simulator. The game places the minutae of traversal at its very center: over different types of terrains, up mountains and down rocky crags, through rivers and around lakes, through snow and sludge. Sam Porter Bridges, as his name so directly suggests, is a courier who builds his bridges and roads and zip-lines with the help of a vast multiverse of other Sam Porter Bridgeses. Traversing what, exactly? Well, a postapocalyptic United States destined for mass extinction, in which a cataclysm has severed the bridge between life and death and “stranded” the dead behind. Ghosts called BTs linger in this world — creatures of antimatter awakened by time-accelerating rain, that catastrophically annihilate at contact with a living being.

Or, in other words, Death Stranding is a game about isolation in the aftermath of disaster — about conditions that drive the fracture of human society into shelters and bunkers and towns, and the people that link those settlements together. Sam Bridges is a deliveryman; he moves supplies, from medicine to food to CDs and video games, between the homes of those that make them and those that want (or need) to consume them — all the while donning a special suit and hood that protect him from that petrifying rain. Death Stranding, in short, imagines a world in which physical connection — and the intimacy that comes with it — is not only impossible, but potentially deadly. It was released on November 8, 2019: 53 days before the first case of COVID-19 was diagnosed in Wuhan, China.

And in service of that theme: interconnection in the face of cataclysm — Death Stranding employs a kind of Dark Souls-ian asymmetric multiplayer. The structures that Sam builds to help navigate his world, from bridges and postboxes to zip-line networks, generators, and highways, don’t just remain in his world. They bleed over into other players’ games, until the act of interconnecting this postapocalyptic America becomes a communal experience. Your own structures take up “bandwidth,” but other players’ don’t. Roads cost an astronomical amount of materials — but, working together, players can pave the whole continent in a couple of days. While its plot drives Sam through a grandiose story about government and history and duty to a country that no longer exists, its mechanics drive a more nuanced and — from my experience — more affecting point home.

https://platform.twitter.com/widgets.jsDeath Stranding is basically propaganda for New Deal-types because the entire game is about the joy of creating infrastructure with other people.

— chris (@canonicalchris) December 4, 2019

Also I am apparently exactly that type because it sure as hell works on me

I tweeted this towards the end of my playthrough, a few months before the world outside began to mirror the game’s strange vision of America. In returning to it, I’d like to make an addendum. Death Stranding is a game about infrastructure, yes, but not in the way management games like SimCity or Mini Metro are. Those games revel in infrastructure itself: in its intricacies and networks on a macroscopic scale. Death Stranding is about the work of making infrastructure, and the way infrastructure can shrink a once-daunting world. It’s about setting out from Lake Knot City and immediately being ambushed by an everpresent pack of thieves — and, 20 hours later, whipping past them in your own personal truck, on a shimmering, elevated highway, covering the same treacherous ground in a few easy seconds. Its power fantasy is a simple, yet enduring one: the ability to both sow the seeds of connection and reap their eventual benefits. To live to drive the road you built, brick by brick, with a thousand of your closest friends.

***

Anticipated for nearly as long as the Nintendo Switch has existed, Animal Crossing: New Horizons arrived at an impossibly perfect time. Released on March 20, 2020, a week or two into the COVID-driven lockdowns that would characterize the year’s spring, summer, and — for us in the United States at least — its entire scope, New Horizons was escapism commodified. In the face of both physical and social isolation, it provided a colorful, effervescent virtual space in which to build and grow and belong, as well as a way to interact and connect with any friends who’d also decided to make that island life their own. Aesthetically, practically, essentially, it was Death Stranding‘s exact opposite: a cheerful, utopian paradise that allowed us to leave every inkling of our pandemic-striken world behind.

That is, on the surface at least. Because well before Death Stranding began its long and tangled development cycle, Animal Crossing was already a game about community, and building, and work.

At the beginning of each and every Animal Crossing game, the player’s avatar moves to a new community. And in every instance, they’re greeted by an old, jolly tanuki named Tom Nook.

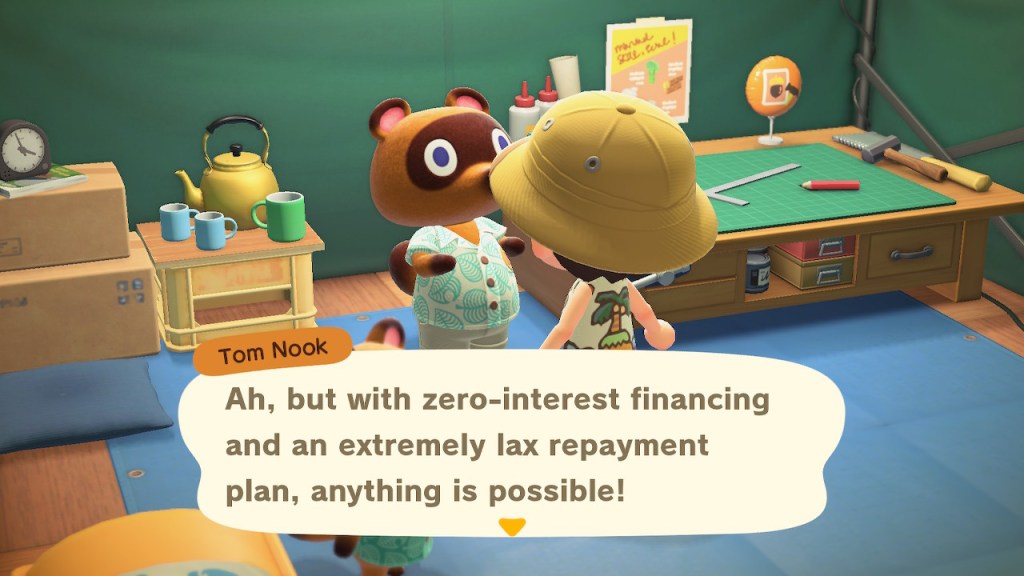

This Tom Nook is an interesting fellow. Invariably, because you — the player — are such a silly human, you failed to secure a place to live in your new town or city or island. Tom Nook gladly provides you with one… and in the process, he tricks you into a mortgage you’ll spend the next hours, days, even weeks, paying back. Tom Nook is many things — realtor, banker, merchant, contractor, and basically everything Animal Crossing needs him to be to set up its core fantasy.

Work.

Of course, Animal Crossing‘s is a different kind of work than Death Stranding‘s; instead of communally building shared infrastructure, AC:NH tasks the player with fishing, collecting, digging, and catching. You can sell your own island’s native fruit, and — if that’s not enough — you can trade with your friends for theirs, which sells at a higher price. You can spend hours fishing for rare sea creatures off the island’s beaches and docks, or creep through flower patches carefully plotted to attract the most precious of bugs. You can dig for the minerals you need to craft more tools, and chop down trees that will always, if slowly, systematically repopulate your island paradise. All of these things are work — they’re daily tasks undertaken to sell for currency, or to fill a museum, or decorate a house. But it’s never forced, and that’s the fantasy.

You see, when Tom Nook gives you that mortgage, he never actually requires you to pay it back. There’s no interest, no due dates or deadlines. The only reason to pay it off — as well as all the subsequent debts you can acquire from him — is to eventually be able to build a bigger house.

There’s no real need to work in New Horizons, or any other Animal Crossing game. You work — returning daily to take on a half-hour’s worth of chores, to chat with your residents and visit Tom Nook’s ever-cheerful shop — because, in some strange way, it’s fulfilling. Animal Crossing achieves that equilibrium by prying work away from subsistence; in this fantasy, your basic needs no longer exist, and you’re free to work however you see fit, for whatever you see fit. And it’s fun — because work that is chosen, without capitalistic threats of thirst or starvation or houselessness, often is.

And in a year like 2020, where work saw all its smoke and mirrors stripped away, games like these are more important than ever.

***

Work, jobs, and labor have, in a way, been the biggest theme of the COVID-19 pandemic. When people can’t interact in person without putting others in danger, some industries collapse while others see their burden magnified. More importantly, classes become more stratified — from the start of the pandemic onward, middle class office jobs were able to retreat to the relative safety and peace of online, remote work. Meanwhile “essential” work, typically in working class settings like restaurants, retail, transportation, and delivery services, continued on with whatever protections could be thrown together. Even with vaccines on the horizon, health care workers continue to face dangerous conditions day-in and day-out. And of course — when industries collapse, some jobs don’t survive. Unemployment skyrocketed, and with it did dangers like eviction, starvation, houselessness. Those same needs that a game like Animal Crossing peels away — that all games, in essence, peel away — stand in stark relief.

Those dangers are, to be clear, not some inevitable tenet of reality. They are the direct result of systems that value production over life — and allow employers to hold their employees’ lives as collateral for their labor. There’s no mystery as to why the United States hasn’t experienced the same recovery as most of Europe and Asia; runaway capitalism, in which government exists to support business and not the lives of its people, will do that in the midst of an existential crisis. We are here, in 2020, because we were brought here. And that won’t end when the sun rises on 2021.

There are two quotes that, in the process of writing this essay, I’ve called back from the depths on my brain. The first was delivered six years ago, in 2014, when Ursula K. Le Guin received the National Book Foundation’s Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters. In her acceptance speech, she said the following:

Books, you know, they’re not just commodities. The profit motive often is in conflict with the aims of art. We live in capitalism. Its power seems inescapable. So did the divine right of kings. Any human power can be resisted and changed by human beings. Resistance and change often begin in art, and very often in our art—the art of words.

The second is from eleven years earlier, when Frederic Jameson wrote a similar sentiment into a piece titled “Future City”:

Someone once said that it is easier to imagine the end of the world than to imagine the end of capitalism. We can now revise that and witness the attempt to imagine capitalism by way of imagining the end of the world.

Both Death Stranding and Animal Crossing imagine a kind of ending. The former: a more traditional vision of apocalypse, with a fractured society on a track to extinction. The latter: a more abstract ending — an end of needs and wants, replaced with something that one might be able to call “honest” work. Neither excised capitalism from their narratives — after all, like Le Guin said, its power seems inescapable. But it’s a start.

Something else ended in 2020 too — a show called The Good Place, which over its four seasons tried to imagine the nature of heaven and hell. Its final conclusion was somber: that an endless afterlife would itself be unfulfilling. That once humans were able to do everything they’d wanted to do — anything they wanted to achieve, whether that be a perfect game of Madden or an understanding of the universe or simply a gesture between the people they love — they should be allowed to end their journey for good, and find eternal peace. It is, at once, a simple yet incredibly radical notion — that we could and should live, and end, in service to ourselves.

Of course, in a year like 2020, that prospect has never felt so far away.

I came to your blog to read about Hollow Knight lore, and left reading this piece feeling both validated and exhausted. Extremely wonderful read, thank you for writing. I am highly educated and experienced, but had recently moved to a new city right before the pandemic hit, and had what was supposed to be an in-between food service job. I then worked that “essential worker” high stress food service job for the entire 2020 year, and am still there in 2021. Education levels aside, everyone I work with feels this pressure of society, of work, of the balance between their own humanity and family and life, and the horrible necessity of work to keep living. There’s jealousy even, of those on unemployment or working from home. Misplaced I feel, because the system is really to blame, but we’re all struggling regardless of the input-output we’ve personally put into the system. Community development without tax is a dream. Escapism into both the apocalypse or paradise are a dream.

LikeLike