[Over the next few months, I’ll be playing through every Metroid and Metroid Prime game, most for the first time. These essays are my observations — my ship’s log, so to speak, of this journey. Join me for a deep dive into seminal series of video games: one that has, maybe more than any other, pulled the strings behind nearly three decades of game design.]

In this post: Metroid (NES, 1987)

Next: Metroid II: Return of Samus (GB, 1991)

***

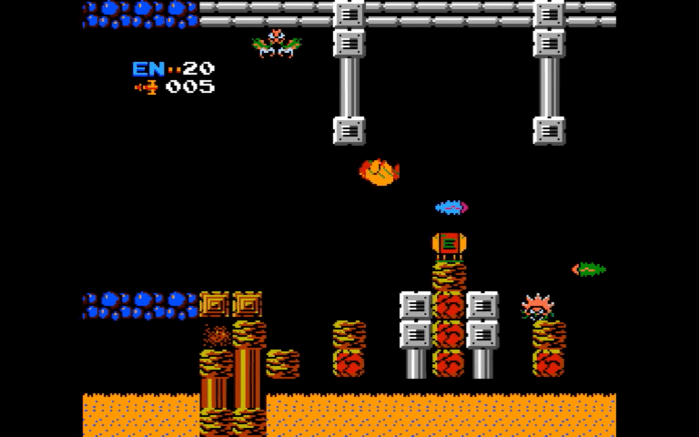

If I were to describe the first Metroid in a single word, it would be hostile. Most of the games the series has inspired present the player with treacherous, occasionally confrontational worlds — but very few are as actively antagonistic as this one. This isn’t limited to enemies, though they certainly embody it — and they create an environment where direct combat tends to take a back seat to careful platforming and avoidance. Everything moves in predictable patterns; once you commit those to memory, you can weave Samus through corridors and rooms with, if not ease, a very satisfying kind of hyperfocus. However, those corridors and rooms themselves also conspire against you: this map of Zebes, a planet we’ll return to multiple times in the series, is laid out like the insides of a Pharoah’s tomb. Vertical shafts lead to multiple identical passageways — some extending only to dead ends, while others hide crucial upgrades. Metroid wants to disorient you, to leave you confused and scared and wondering wait, have I been here before as you backtrack through its labyrinthine world, and the result is an environment that feels like its own kind of enemy. And its lack of a visual map — a design choice almost unheard of in decades since — is essential to that feeling; all you have to rely on is your notes and your memory, and both are set up to let you down.

Metroid is, of course, an old game — from the tail-end an era of mechanical difficulty intended to pull quarter after quarter into an arcade cabinet’s reservoir. But Metroid doesn’t play like an arcade touchstone, nor like an early console game like the original Legend of Zelda. That game may be difficult, but it doesn’t play with the same kind of disorientation — or the same frantic avoidance — that gives Metroid its atmosphere of isolation. Its overworld design propels Link forward from secret to secret, dungeon to dungeon, funneling him ever-toward his eventual clash with Ganon. Nor does Metroid mirror the difficulty of early Mario games — those games are difficult in that very arcade-y way, mechanically tough but constructed with skip after skip in level after level. You can beat Super Mario Bros. in 8 levels — and once you know where to go, you’ll never be lost again. Metroid instead finds its difficulty in inspiring doubt, in confusion and misdirection; it feels like it’s trying to chew you up and spit you out again, with invisible floors above acid pits and brutal, relentless enemy movement and crucial upgrades locked behind secret after secret. And I love that.

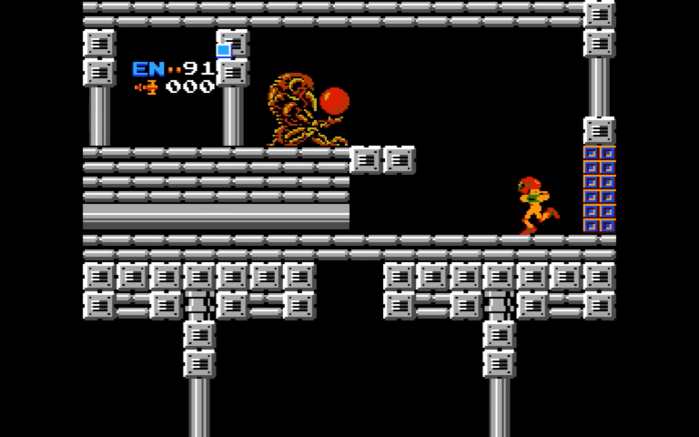

And as Metroid puts its efforts into confusion and disorientation, it of course isn’t above changing its own internal rules. The titular metroids — gated in the final area, only accessible once you’ve explored the entire map, faced two challenging bosses and virtually every other enemy the game has to offer — are its most terrifying invention. Every enemy in the game moves in a predictable pattern, with either smooth arcs or right angles easy to jump, duck, or run past. The metroids, on the other hand, make a beeline straight for Samus’s head. Fail to freeze them quickly enough and they’ll attach and immediately start draining the life (or, well, energy) from Samus’s body (or, well, suit… put a pin in this one). The only way to detach them is to curl into a ball — a strangely fetal response to a deadly threat — and drop bomb after bomb until they detach. And then you’ll have a split second to freeze them again before they reattach again and again and again. Metroids are horrifying and monstrous in a way very few video game enemies have ever felt to me; the fact that they’re framed as largely innocent — a kind of native fauna with an innate survival drive manipulated by malicious forces — also makes them feel strangely tragic. Let’s put a pin in that as well. Perhaps, just maybe, there’s more to them than it seems.

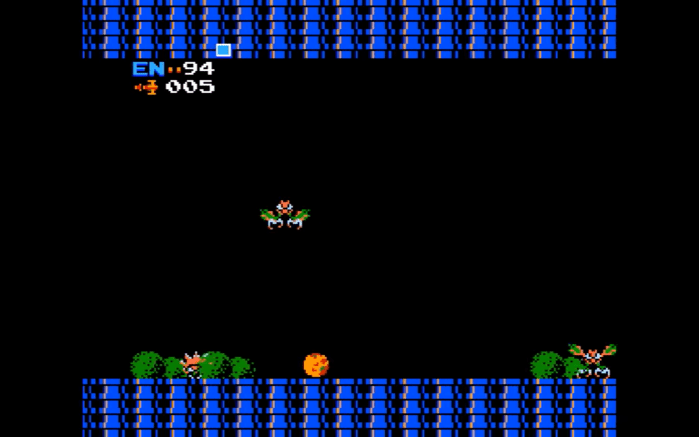

Incidentally, I did do something to make the game a bit more approachable — I read the manual. It always surprises me just how much information game manuals from the 80s and 90s held — much of the reason that these games might seem obtuse to modern players is that a lot of essential info is just written down, to be delivered outside the game itself. Every power-up is listed, all the enemies and core mechanics, and, especially importantly, the way to kill Metroids once you reach them. I also adore the NES-era pixel art, but some of the strangeness of these creatures does get lost in it — I think their full weirdness (especially Ridley’s, who apparently has a bunch of long eyes all down his snout??) can only really be appreciated in these sketches.

And I did make it through! All in all, my 3DS clocked in the run at just under 5 hours — so I did get to see Samus’s face in the end. And let’s talk about that for a second; the manual goes to great lengths to hide Samus’s gender. As does the game itself; when Samus dies, her suit just explodes into bits, seemingly with nothing inside. In a way, it makes Samus seem almost like an android, a robot, nothing but the suit that’s enabling her survival in a harsh, unforgiving planet that also happens to be her birthplace. (And let’s put a second pin in that: death animations are going to come up a lot when I talk about future Metroid games — they’ve always felt weird to me in quite a few ways). Mother Brain, also, is referred to as “he” in all the supplemental text — something that we may be coming back to when she reappears. In any case, I’ve seen all the ending screens; the game treats the reveal of Samus’s gender as a parlor trick. “Surprise,” it says, “you were a woman this whole time.” And of course, finish faster and the game delivers some fanservice. Let’s put a pin in that too.

Also yes, according to the manual, Zebes is where she was raised. Metroid is about a homecoming: a return and, in a way, a liberation of an overtaken world. All the artifacts, the power-ups (as the manual calls them, though “upgrade” is the term that would come into vogue) seem to inherently fit Samus; she requires no training, no additional expertise, nothing but the materials she finds to make use of them. And this lays out the power fantasy that makes Metroidvania games so compelling for me as a player — the reduction of an environment from impossible to challenging to easily traversable as more and more of it is uncovered. That fantasy is incredibly bold here, largely because the game itself is so simple. Obstacles that took me painstaking effort in the first hour or so melted with the help of the wave beam, varia suit, or especially the screw attack, which trivializes what felt like 90% of the game’s enemy variants. It was a distinctly familiar feeling — one that reminds me of a game that, while not explicitly a Metroidvania, clearly pulls its design inspiration from the Metroid and Castlevania trees. A game that the first Metroid reminds me of, more than anything else, more than Alien or Axiom Verge or any other sci-fi horror game or film or property in existence.

I’m talking, of course, about Dark Souls.

This exact arc, the backtracking, the slow escalation of a finely-tuned power fantasy constructed around a newcomer in a hostile world, the emphasis on confusion and misdirection and isolation — hostile to the point of actively trolling the player, constantly treacherous and unsafe, with pitfalls and trapdoors and enemies placed just-so to destroy you when you feel safe… it’s eminently familiar to me, to the point where the reason I was able to make it through this time was the two years I’ve spent playing and replaying my way through the Soulsborne canon. I reached a point about an hour or so into Metroid, as I kept falling through invisible floors into a lava pit, where I thought this game just wants to fuck with me. In that moment, I had a vision of a giant Bloodborne werewolf jumping out from its invisible post off-screen to push me off a cliff to my death — and it clicked. I knew where I was, what I was here to do, and exactly how the next few hours were going to go. A bit later, when I realized I could cheese Ridley by chilling in the acid beneath his platform and shooting the wave beam upward, I just smiled and watched him disintegrate. Dark Souls had taught me well.

2 thoughts on “Metroid, and the Art of Getting Lost”