[Over the next few months, I’ll be playing through every Metroid and Metroid Prime game, most for the first time. These essays are my observations — my ship’s log, so to speak, of this journey. Join me for a deep dive into seminal series of video games: one that has, maybe more than any other, pulled the strings behind nearly three decades of game design.]

In this post: Metroid II: Return of Samus (GB, 1991)

Next: Super Metroid (SNES, 1994)

***

Let’s talk, for a moment, about music. Metroid II does a really specific thing with music, something I noticed almost immediately but didn’t think much about until I was over halfway through the game. It’s the track “Surface of SR388” — and it follows you through almost the entire game. Each set of caverns, those hubs with their dead-end spokes that branch off the game’s main path, has their own track. But whenever you venture back onto the critical path that leads down into this ever-deepening underworld, that track blasts back into prominence. In a way, it’s the black sheep of a soundtrack filled with harsh electronica, with almost mechanistic melodies that seem to contain more empty space than they do actual notes (mirroring, in a strange way, the sparse lifelessness of SR388’s caverns). “Surface,” instead, is a driving, earwormy melody of the same chiptune heritage as Brinstar’s theme from its predecessor. A constant companion as you push deeper into this alien world, it pushes you onward, farther deeper — it is, in a sense, a sound of progress. The thing that, post-earthquake and slaughter, orients you back onto your downward trek.

Very fitting for a game that — in a very precise, exacting, even clinical way — is about committing genocide.

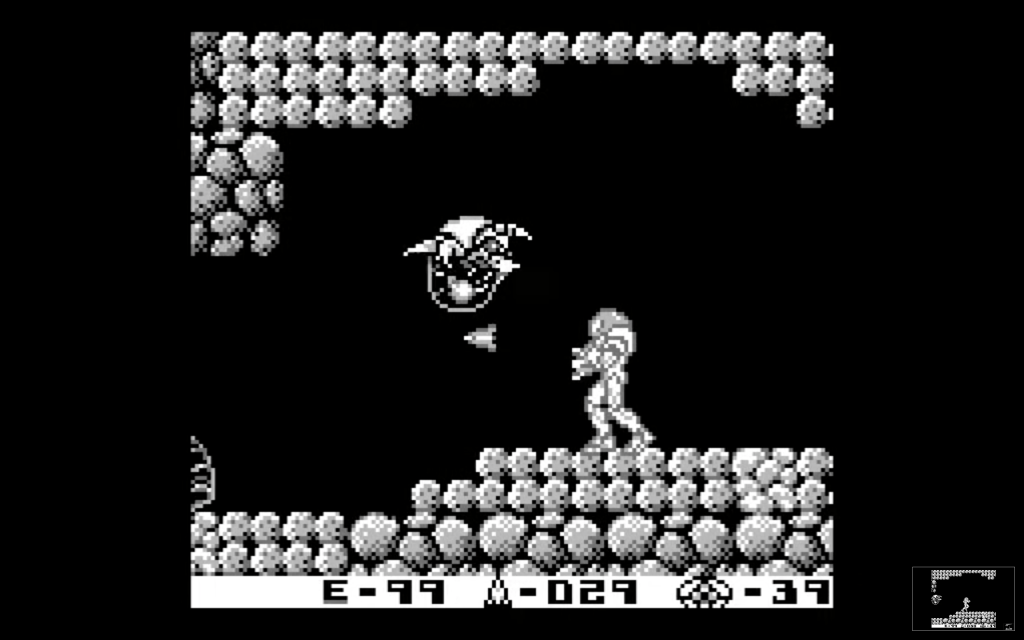

There’s nothing else to call the events of Metroid II (and, to its credit, the game knows that). Despite the limitations of its tech — the big, blocky tiles, the complete lack of color — it’s very clear about certain things. The metroid carapaces Samus encounters throughout the underground — empty shells that mirror the first mid-molting metroid she finds near the surface — serve as a constant reminder of the lifecycle happening in the depths of this planet, the very lifecycle the game directs you to interrupt. And towards the end, when the counter reads six metroids remaining, Samus enters a large, open arena with two such shells but only one Metroid. It’s only when Samus kills it and loops back around (having found that the planet’s acidic water table has risen to trap her in this loop) that the second, stronger one appears. The original game makes metroids seem almost autonomous and robotic — machines born from machines, built only for draining life. This moment, on the other hand, says that these are creatures with bonds; they notice when one of their number is felled; when they do, they mobilize to defend their home. The fact that their home is set up like a hive, with a “Queen” at its deepest reaches, even implies a kind of eusociality. And this is their home, a strange mirror to Zebes in Metroid. In that game, Samus had returned home an exterminator, rooting out an infestation; in this one, she’s gone into their home, aiming, in no uncertain terms, to eradicate an entire species. And as that counter ticks ruthlessly down, that song is a constant companion, giving direction.

Onward.

So when, after concluding that extermination, Samus comes upon the metroid hatchling — the change that hit me most was the music. The hatchling’s theme is peaceful, calming, without a hint of danger or malice. In a word, it’s uplifting.

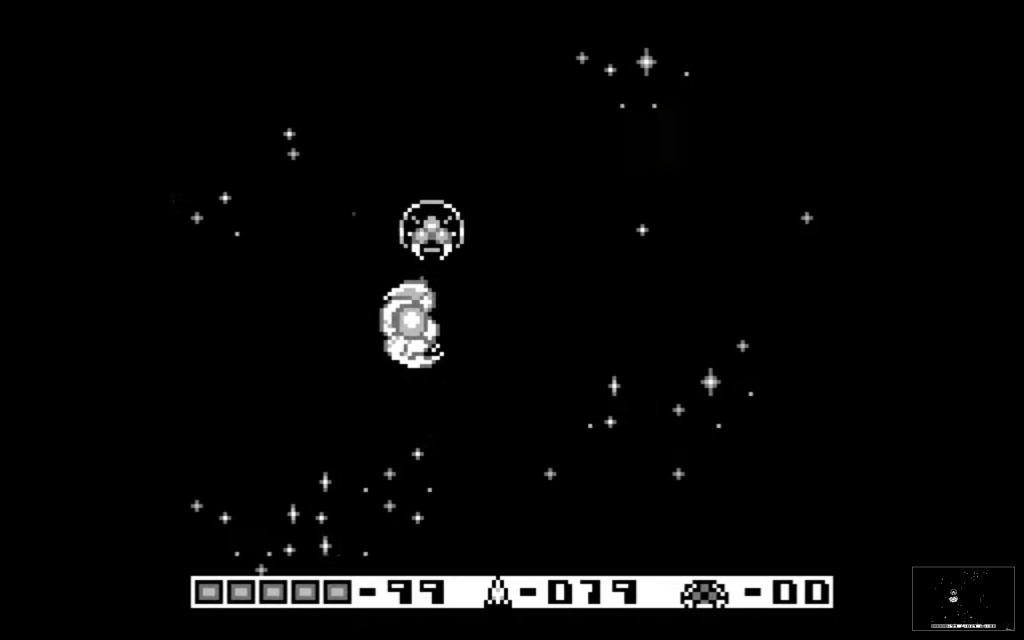

And suddenly, after hours of descent into the depths of an infernal planet filled with acid and armored monsters, the way forward is upward. The music itself lifts upward. And when Samus and the hatchling burst through the final barrier, the sky above SR388 is filled with stars.

There’s something eerily beautiful about the ending to this game. In a way, it does mirror the first Metroid — the shafts filled with metroid larvae that appear just before Samus fights the queen feel much like the entrance to Tourian, and it fills the space after its final boss with an ascent. But this ascent isn’t timed and frantic; it’s really the only moment of peace this otherwise relentless game has to offer. It also is the only moment the game forces Samus to wait for anything, as the hatchling gnaws through otherwise impermeable barriers. It is, in a way, as if it’s asking her to stop and recollect — and it comes as close as it can to a feeling of revelation.

***

Loose Thoughts and Threads

- There’s a pattern with certain long-running Nintendo series — in particular, I know it holds with Mario and Zelda — in which the second game is always the weird one, the odd one out, the one with room to experiment before that series’ formula finally crystallizes. I tend to be fond of these games; The Adventure of Link, in particular, is a longtime love of mine, and perhaps the one NES-era game I’d most love to see remade with the tools and framework that could really bring its loneliness, its strangeness, and its gargantuan sense of scale to life.

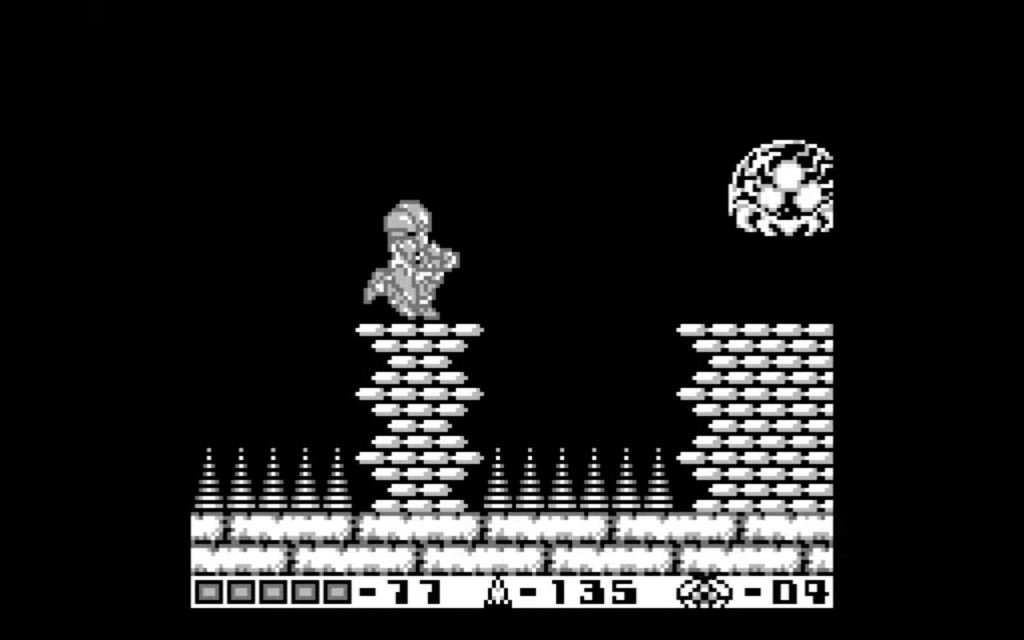

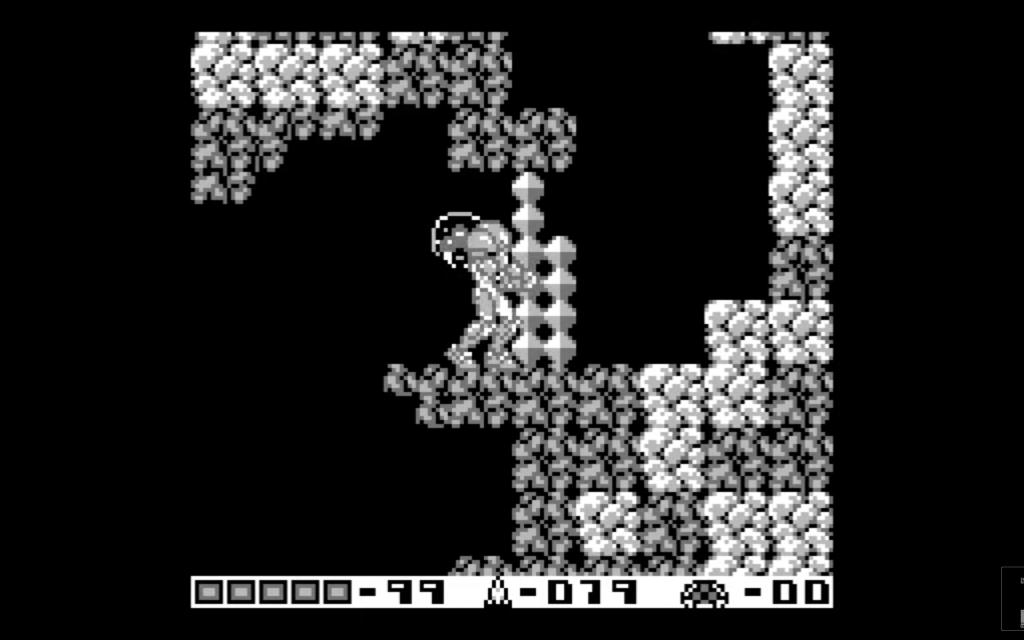

- (Of course, I could argue that Breath of the Wild actually does kind of do that already, but that’s neither here nor there.) In a way, Metroid II lines up with that pattern. As I’m diving into it directly after finishing the first Metroid, the ways its design diverges stand out in stark relief. In comparison, it’s an incredibly linear game; the areas themselves may have some branching paths, but they essentially follow a miniature hub-and-spoke design, with power-ups and objectives scattered at the ends of dead-end paths. In the end though, after an area is cleared and the ground does its brief shaking, there’s only ever one way forward — usually down, further into the depths of this planet, the metroid homeworld SR388.

- But I have to say that, in comparison to the first Metroid, I’m not incredibly gripped by the world and level design here. It follows that pattern by being different from the first game in its series, but in a lot of ways it feels markedly less risky. At the halfway point, I’ve acquired what feels like almost every power-up in the game (the only one I seem to be missing is the Screw Attack; otherwise, I’ve found every ball and jump upgrade and every beam type at least once). And the linearity, perhaps ironically, isn’t doing the greatest job of pushing me onward. I played the first Metroid more or less in one sitting — driven forward by the way it really masterfully looped together twin senses of mystery and discovery. Its friction was good friction, intentional friction: the hostility I talked about, the way its upgrades cascaded with each other, giving me new ways to explore the world and a sense of mastery over familiar spaces. That doesn’t really exist here — in a sense, this feels like a much more conventional, level-based action-platformer. It is, in a word, pretty familiar. If it weren’t as short as it was, and I hadn’t been giving myself this challenge, I likely would have put it down a little while ago.

- So, what is unique about this game? The easy answer is the metroids themselves. In an early chamber just underground, Samus comes across a giant, glowing metroid — identical to the ones in the first game, but much larger. However, as it turns out, that familiar shape is just a shell, a shell it quickly molts from to reveal a kind of crustacean-like carapace and beak. The little counter at the bottom right of the screen makes it clear that Samus is here to kill it — and, when she does, an earthquake sounds, draining the damaging liquid from the passageway down. 39 left to go.

- I can see why this game has a virtual stable of remakes. In theory, its elements fit together almost perfectly; the linearity works in tandem with this motif of descent, and it really does make Samus feel like an invader, stopping at each little metroid refuge to destroy whatever’s lurking there. There’s enough here to piece together some really compelling moments (not the least of which is Samus becoming, essentially, this hatchling’s surrogate mother moments after killing its biological mother). And there’s a lot of understandable friction; metroids are difficult to kill, and they only become more difficult as the larger, stronger, higher-stage ones emerge deeper into the nest. They feel like trapped animals, and, in that way, the way these boss fights play out does fit the game’s narrative bent.

- However, there are still a lot of ways that friction doesn’t work. For one — it just feels stuck between being a fully linear, level-based game and embracing the backtracking that the first game made more or less mandatory. As such, Samus must kill each metroid to progress — working that counter downward and downward until she evidently destabilizes this planet’s ecosystem enough to cause an acid-draining earthquake — but power-ups, missile upgrades, and energy tanks can be entirely missed. Or (as I did several times), she can run out of missiles without any nearby replenish points, requiring a lengthy backtracking session with no purpose other than to refill a gauge. It’s tedious and unsatisfying — which one might argue fits with the nature of the mission, but I didn’t sense anything else in the game reaching for that kind of synchronicity. (And, in any case, I found it unsuccessful.)

- The boss fights themselves, while atmospherically fitting, also do start to wear out their welcome after a while. The omega metroids in particular just felt frustrating; their hitboxes are strange, their paths through their arenas are erratic and unpredictable, and in the end it felt like cheese was the only reasonable strategy (and this is with me liberally utilizing the 3DS’s save states). If I didn’t have access to those, I could have “gotten gud” at these fights I’m sure… but the likelier outcome is that I would have just put the game down and played something else.

- That’s to say that I’m looking forward to both AM2R and Samus Returns, since now I have the context to understand what they’re building from. From what I remember, Samus Returns kept the general structure but played fast and loose with quite a bit of this game’s design — to the point where it’s more reimagining than remake. (Knowing what comes at the end of that game though, I kind of prefer this ending, and the peace that it leaves off with.)

2 thoughts on “Metroid II: Return of Samus: Crafting the Genocide Run”