[This post is the second entry in my Twelve Months, Twelve Games essay series, and contains spoilers for the entirety of Videocult’s survival platformer Rain World.]

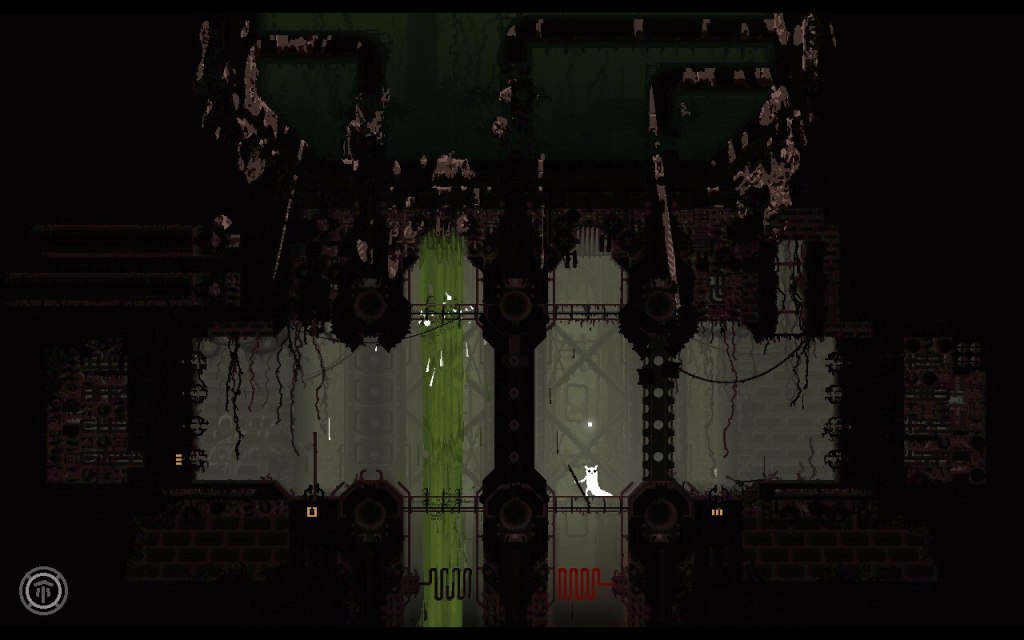

Deep in Rain World‘s midgame, I found myself at the base of something called The Wall. An hour or so earlier, I had missed a gateway meant to take me through the game’s intended path — through the gravity-defying innards of a massive supercomputer called Five Pebbles — and had instead begun the process of an arduous and entirely accidental sequence break. The Wall, I later learned, is designed to be descended; the game’s protagonist, a small, strangely viscous animal known only as the slugcat, emerges at the top of the massive structure it had scaled and — after witnessing the emaciated husk of a long-dead city above the clouds — begins the hazardous process of making its way back down. On that journey, it drops past hungry lizards and carnivorous plants, drifting back below the ever-present raincloud layer that gives the game its titular hazard. The Wall is harsh, unforgiving, and desolately beautiful: a short sequence of careful dives and controlled falls as the sky once again disappears behind its shield of clouds. It is Rain World‘s mission statement, and the initial piece of a long descent below the earth that makes up the game’s final act.

But, if you encounter it as I did — from its base, not its apex — you might instead find yourself trying to climb.

***

Rain World has a certain reputation in the gaming sphere: a hellishly difficult 2D platformer largely panned by critics at release, but that found a second life via a relatively small and deeply dedicated community of fans. I had tried to play it several times over the past few years, emboldened each time by various accomplishments in other “difficult” games — and each time I found myself unable to make it past the first few levels. This time, I broke through with the help and advice of some friends on the Waypoint forums, and behind that initial wall I found a piece of art that, especially in its “remixed” form, has more to say about that idea of video game difficulty than any other game I’ve played.

Video game difficulty has become a… touchy subject, prone to thousand-reply tweetstorms and radioactive Reddit threads, and my feelings on it are complicated, idiosyncratic, and constantly evolving. I largely feel about games the way I do about other kinds of art — that artists should create projects that compel them, while understanding that their choices might restrict the audiences they reach. Accessibility should always be a base concern: one that manifests in options like control remapping, colorblind modes, and other options that allow players to adjust the ways in which they interface with a game’s core systems. At the same time, I find conversations around difficulty often boil down to the importance of mechanical skill — whether someone playing a precision platformer can hit the proper inputs, or think quickly enough to react to a Soulslike boss’ attacks — and I find that distillation quite unsatisfying. There are many other ways that games make themselves inaccessible to different types of audiences: ways that seem chronically overlooked when this discourse inevitably comes around. One particularly common one is time. I used to love JRPGs — as a child with few responsibilities and more or less unlimited time — but I more or less swore them off after I left high school, because dedicating a hundred hours to grinding through a game’s campaign carries opportunity costs I can no longer pay. I’d love to finally play Persona 5, or take a stab at Bravely Default, or make it through Shin Megami Tensei III after starting it a bunch of times — but doing so would mean passing up too many other options, especially without knowing if it’ll all feel worth it in the end.

Still, I don’t begrudge developers who design hundred hour games; if that’s the decision they’ve made, and the framework they deemed necessary over the years of bringing their creation to life, I’m not going to question that creative choice. I feel the same way about Dark Souls — a series that I’ve written several posts about (and then made the basis of my my MA thesis this past fall), and, like Rain World, a game that took me multiple attempts to really come to love. In the end, difficulty is just another tool: one that comes with potential and responsibility, and one that developers can wield in a variety of ways to tie into a game’s narrative concepts and ideas.

Rain World builds its progression around a system it calls “Karma,” shown by the circular icon at the bottom left of the screen. Karma increments with each successful hibernation; its level ticks up by one each time the slugcat manages to make its way to shelter before the rains come pouring down. This, in combination with finding just enough food for a successful sleep, comprises the game’s core loop — oriented around cycles of survival in an unfeeling ecosystem, as the middle rung of a simulated food chain. The slugcat is an omnivore, able to consume bugs and plants alike, sometimes even hunting similarly-sized fauna for different types of food. Sleep with a full belly before the monsoon comes, and the game marks your success: your karma increments, as do the numbered cycles, and you awaken in the shelter ready to do it all again. Fail to do so, and instead your karma drops with each successive death, often generating a feedback loop of dying again and again and again.

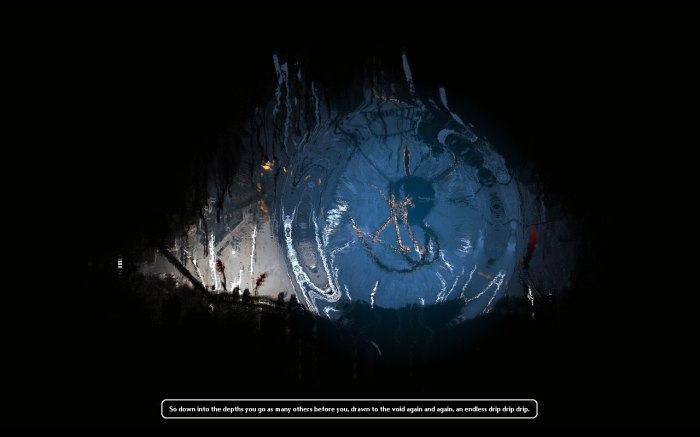

Karma, of course, is not a concept endemic to video games; it’s a principle originating in several Indian religions and spiritual systems (perhaps most famously Buddhism, but also Hinduism and Sikhism, among others). In those contexts, karma typically revolves around cycles of rebirth; it measures and marks the choices of an individual in one life to influence their circumstances in a new one. It is a mark of action and intention, and designates future consequences. In Rain World, a game deeply informed by Buddhist thought, its simplicity undergirds a set of much more complex systems — affinities with various groups of animals, ledgers of the types of food for which your slugcat hunts or forages, and even types of lizards you’ve found ways to kill. But it functions much the same way it does in earthly contexts: the action of successful hibernation leads to higher karma, and with it the ability to pass through the many gates that separate the world’s different regions. To complete the game, the slugcat must reach Rain World‘s maximum karma level — 10, symbolized with a simple circled X, and acquired only after visiting the creature at the top of The Wall and gaining the ability to communicate with others. Doing so will unlock the game world’s deepest point: a region called The Depths, filled with strange, eldritch beings, distorting smoke and fog, and a vast abyssal lake: a void beneath the earth. Sinking beneath that void completes the slugcat’s ascension; it escapes the cycles of suffering that drive its post-apocalyptic world, sheds its mortal form, and finds — to continue with the game’s Buddhist framework — its own version of nirvana.

***

I don’t intend my point to in this essay be something as simple as “the game about suffering must be hard” — that’s the kind of tedious conclusion people often cite defending “difficult” games like Dark Souls, and as with those cases, I think it’s a rather weak and boring observation. But Rain World does gain something tangible from the ways in which its difficulty manifests. The game sources its challenges from several different locations: its movement system is opaque and, at first, clumsy; its fixed angles and travel pipes (a bit reminiscent of Metroid doors) make noticing off-screen enemies and hazards challenging, the the procedurally-placed nature of its creatures and food sources make it hard to ever fully know what you’ll find around a corner. While visually-similar platformers like Celeste and The End is Nigh orient their level design around a perfect run, and bossfight games like Furi and Cuphead present the fantasy of a perfect combat encounter, Rain World makes perfection itself a stumbling block to self-fulfillment: an impossible goal for which it knows its players have likely been conditioned to strive.

In some ways, a player new to video games might have an easier time acclimating to Rain World‘s brand of difficulty than someone who’d spent their whole life playing them, because Rain World simply does not play like other games. It rejects the power fantasies that undergird Soulslikes and many 2D platformers in favor of an ethos that emphasizes mere survival over the euphoria of perfection. Its best stories, its best moments, aren’t oriented around a perfect dance with an enemy or a frame-perfect dash through a screen filled with hazards; they arise from the unexpected systemic interactions between some strange object you picked up and a lizard hoping to make your slugcat its dinner, or from the chaos of escaping from a horde and crawling into a shelter just as the rains begin to fall. Rain World‘s rare bits of lore revolve around a set of ancient beings, all trying to escape an endless cycle of rebirth as their world collapses into rot around them. Eventually, that too becomes your quest. But Rain World‘s only measure of progression towards that goal is karma — and karma is simple, rising with hibernation and dropping with death, and remains uninfluenced by the ways in which the slugcat survives the world around it. In the end, Rain World‘s difficulty lies in recognizing that true goal, and in understanding that any impulse towards perfection needs to be abandoned; instead, it emphasizes learning flexibility and patience, reacting with instinct to the game’s unexpected hazards almost like the animals at its core. This is Rain World‘s nirvana: an approach to difficulty and narrative entwinement that few games I’ve played come close to matching, and an dismissiveness toward the ideal of perfection that stands out amid a swathe of gaming power fantasies.

And yet, there’s still another angle to Rain World‘s success with difficulty: one encapsulated in its recent Remix update, a collection of accessibility options that, without which, I probably never would have tried the game again.

***

This past January, Videocult and Akupara Games released a long-awaited DLC expansion for Rain World titled Downpour. Featuring a set of new slugcats and campaigns through redesgined versions of the world, Downpour also shipped with a free update called Remix — a collected set of tweaks, adjustments, bugfixes, and difficulty sliders that allows players to adjust several aspects of Rain World‘s play. The update, available to anyone who owns the base game, consists of several lists of checkboxes that modify aspects of the game’s world — some making it more accessible, some making it difficult, and some just meant to improve the game’s general feel. For one, the primary way in which Rain World alerts the player to an off-screen danger is by changing the ambient music: adding a threatening undercurrent to the environment’s normal score. One of Remix‘s options adds a visual component — a set of red dots that will appear at the bottom of the screen, the number of which indicates how close an approaching hazard or predator might be, while another shows the rough position of nearby predators on the map when it’s pulled up. When swimming underwater in the base game, Rain World has no visual indicator of the slugcat’s remaining breath; Remix adds a visual meter as an option, making the journey through the game’s many flooded passages more readable. Alongside gameplay options, Remix adds a set of loading screen tips and new tutorials, as well as the ability to change the length of time that passes before rain starts to fall. And perhaps most significantly, it adds an option that it shares with another notoriously hard game praised for its approach to accessibility: Celeste — the option to slow down the game’s internal speed to match whatever an individual player’s reflexes can handle.

While I only made use of some of these options on my playthrough of the game — mainly the added UI tweaks, and, towards the end, the option to keep each cycle a consistent length — two things were consistently obvious: that Remix would open up a notoriously difficult game to a wider audience of players, and that none of those options would at all interfere with the way the game’s difficulty plays into its narrative beats. Rain World‘s thesis, with these options, remains unchanged; collected together, they make surviving in its world just a little easier, but make perfection no simpler to attain. The Remix update was what brought me back to Rain World, with the sense that maybe things had changed from all those other failed attempts. That this time, I’d manage to break through its wall.

And this time, I did — that’s how I found myself at the bottom of it.

***

Rain World does not intend for you to climb The Wall. The act of doing so is a skip: a sequence break popular with speedrunners and those who’ve played the game a million times before. Halfway through the Underhang — the level that precedes it — the game’s progression all but grinds to a halt; there, the designers place a series of almost unfair challenges in an attempt to guide the player upward towards the entrance to Five Pebbles. Only a particularly stubborn set of players would continue chiseling away at them and, upon succeeding, find themselves standing at the bottom of The Wall. Smaller still would be the deeply stubborn subset that commits to climbing it.

As a player, I am deeply stubborn. It’s likely why I click so strongly with games that weave power fantasies from harsh difficulty. It’s why I almost never play hundred hour games, but dumped almost three times that much last year into Elden Ring, why I’ve replayed every Souls game at least two full times, why I’ve worked through every level of Celeste, finished Hollow Knight twice over, and spent five years growing agonizingly closer to finishing Enter the Gungeon‘s true ending. Rain World is like none of those games — it’s a different kind of difficulty for a different kind of story — and though by the time I reached The Wall I thought I’d figured out its own internal calculus, I couldn’t resist that final jab at my own feelings of perfection.

In Buddhist thought, suffering emerges from desire: from craving gratification, pleasure, immortality. And hard games are, in a way, their own promise of immortality — of an achievement that can’t be taken away, that can be broadcast and shouted out to everyone around you. As I tried to climb The Wall, I thought about where it would rank among the things I’ve done in games — the Celeste C-sides, the Gunslinger unlock, the journey through Dark Souls II‘s notorious Frigid Outskirts (which, incidentally, I actually kind of love). Then, as half an hour of failure became hours, as The Wall’s challenges and traps and hub of psychic lizards started to seem not as much difficult as intentionally unfair, I realized it might just never happen, at least not before my own world’s sun began to rise. Eventually, I gave up and went to bed.

The next morning, I decided to backtrack — to take the return path through the Underhang and rejoin the game’s intended route. But there was some easy food a few screens up the Wall, and I wanted to regain some karma fast before I made that trek.

Then, once I’d filled my slugcat’s belly, I thought why not. Why not give it one more shot? I wasn’t expecting much; eventually, I’d fail a jump, or a lizard would burst from its camouflage and eat me. So one last time, I started climbing.

And that time, I never stopped.

A successful journey up The Wall conjures up a special kind of magic: one that the entirety of Rain World helps to bring to life. From the very beginning of the game, the one omnipresent threat is that of rain — the timer ticking down towards the deluge that, if caught outside a shelter, will sweep your helpless slugcat to its doom. At the bottom of the Wall, the sky behind its poles and offshoots shows nothing but thick brown clouds; yet, as you climb, they start to thin and fall away, revealing stretches of gorgeous dark blue sky. Then, suddenly, you’re above them; the timer disappears, and the threat of rain is gone. The hazard that, until this point, defined your slugcat’s existence, that powered this game’s cycles of death and reincarnation, vanishes below your feet. What seemed inescapable and all-encompassing becomes just another feature of the earth. Until you reach the top, so far above it that you see the moon and stars, and all the other structures just like this one spearing through the clouds.

I don’t know if I should call it a coincidence: that it was only when I’d all but given up that I finally managed to climb The Wall. I do know that when I reached the top, I’d forgotten all about perfection — instead, I left myself behind, spellbound by what I saw around me: by the subtle music and the beauty of Rain World‘s view above the clouds, and by my own smallness in the face of something far too vast to name. It hadn’t been a perfect climb, not quite, not even close. But in surviving the journey upward, even if it was a way the game had never meant for me to go, I had taken my own tiny journey of ascension.