[This post is the third entry in my Twelve Months, Twelve Games essay series, and contains spoilers for all of Neon Genesis Evangelion and the Metroid series of video games. It might also be a capstone for my Metroid essay series, which someday I might properly finish.]

Late in every Metroid game, usually as she approaches the core of whatever alien world she’s been sent into to destroy, Samus Aran comes across one last, brutal upgrade. Up to this point, she’s undoubtedly powered up her bombs and missiles and acquired new flavors for her beam cannon; likewise, she’s found suits with the ability to withstand even greater hazards and propulsion upgrades that let her jump endlessly around whatever room she chooses. Metroid builds its power fantasy from these recurrent pieces — composite superpowers with names like the Space Jump, the Gravity Suit, the Plasma Beam, the Power Bomb. Still, that fantasy is never quite complete without one last mainstay: an ability so integral to the experience of Metroid that its lightning-bolt insignia has become the emblem of the series itself.

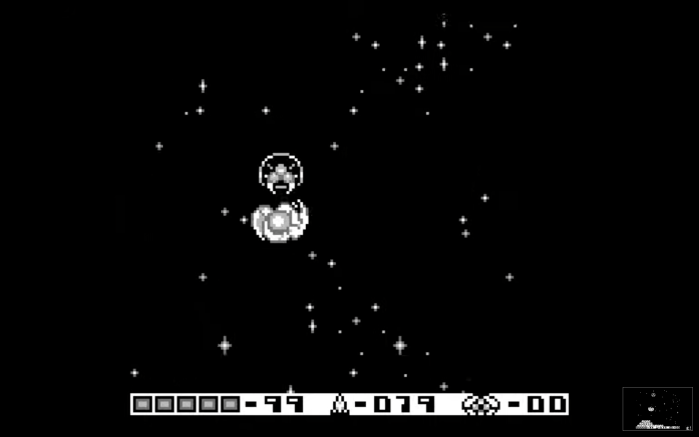

The Screw Attack, which manifests as a devastating electric charge that surrounds Samus whenever she does her signature somersault jump, is the Metroid heroine’s weapon of mass destruction. From the first game in the series to the last, it exists to grant the player unencumbered progress through whatever room or passageway they choose — by instantly vaporizing any alien creature Samus happens to jump into. The games usually represent these with explosions and then absence: little bursts of energy followed by the simple fact that group of pixels that once occupied a space is no longer there. Though, at this late point, Samus rarely hangs around long enough for that absence to be felt.

As a medium, video games are defined by different forms of touch. Both the interface between player and game and the action of most games itself relies upon a set of simple rules — what kinds of responses a particular touch will engender, and what groups of pixels can and cannot be safely touched. Games have their own language for these interactions: collision detection defines the act of in-game touch, and hitboxes measure where and when that touch brings pain. In most games, this becomes a kind of broad and neutral framework: a foundation on which mechanical and narrative structures can be built.

But in Metroid, touch becomes its own singular kind of horror.

***

The Metroid series begins simply, with a long tunnel beneath an alien planet and a protagonist that seems more armored suit than human. In the first game, Samus is her suit; her act of dying reveals no body, just a few metallic fragments sloughing off into the darkness of those passageways. In contrast, from Super Metroid onward, the games spent those moments of repeated dying lingering almost voyeuristically on their protagonist’s unemcumbered form: holding her arched pose and pained scream until the world fades out. They seem to posit that, in this cold and unforgiving universe, bodies, especially this female body, are exceedinly frail things. Touch the cosmos, and they’ll shatter like little more than glass.

Contact damage is the term games use for the pain of being touched, and Metroid finds contact damage wherever it can look. Besides the mossy caves and rocky tunnels that make up each game’s map, virtually everything in the world will send Samus recoiling in pain — another tick of her suit’s energy gone, another step closer to the threat of her own death. Many of the games’ creatures show no outward hostility, just spiky beetles working their way around platforms or flying insects drifting in wave-like patterns across the screen. Moreover, much of Metroid‘s danger comes as much from environmental hazards as it does from alien fauna: from thorns and spikes, acid pools, or veins of lava that wind through planets like deadly circulatory systems. And likewise, the games’ core power fantasy rests on the ability to surmount these different hazards one-by-one — to march through a volcanic cave impervious to heat or blast through an underwater passageway without regard for friction. Others still instrumentalize the ability to nullify the threat of touch: the ice beam, in particular, can freeze damaging creatures into neutral platforms, creating fleeting spots of safety amid an sea of threats. From these aspects Metroid builds a tale of interstellar loneliness, of keeping the world outside at bay from the safety of an armored core, and nowhere is this more apparent than in the series’ second game and its many remakes: Metroid II; AM2R; and Samus Returns.

Metroid II, as I’ve written about before, tasks Samus with a mission of extermination; fresh off the events of the first game (and the prequel Prime trilogy, itself an interstellar horror story about infectious contact), she lands on the metroid homeworld of SR388 and sets about executing each remaining metroid one-by-one. SR388 maintains its own strange kind of ecosystem, its environment left dry and arid by the presence of the life-draining parasites that call it home. Most of its underground remains submerged in acid until Samus exterminates the right amount of metroids; then, the corrosive sea lowers, allowing her to access a new set of caves and nests. In a way, it models the collapse of the planet’s ecological systems: the death of creatures holding it in check resulting in seismic changes to the world’s physical makeup. More importantly to the game’s creeping sense of horror, those changes mean little to Samus at all. Eventually, with a fully upgraded suit, that acid layer itself ceases to harm her. She becomes impervious to corrosion, hardened against every last one of the biosphere’s defenses: a hunter on a mission that, should it succeed, will leave her unflinchingly and unfailingly alone.

Of course, it doesn’t — in the game’s last twist, one lone metroid survives: a hatchling that imprints on Samus at the moment of its birth and floats in a helix around her body as she ascends into the stars. That infant metroid drives the plot of Super Metroid forward to its final battle, in which it sacrifices itself — in a rare, maybe even singular moment of a restorative rather than damaging touch — to save Samus’s life. The Metroid universe is a zero-sum game, one in which Samus maintains her own survival by armoring herself against the outside world. It’s fitting in this horror story that the games’ one moment of real, personal contact with an alien species leads to its destruction.

This tableau — of hostility and danger and a kind of existential loneliness — forms the base of the Metroid series’ unique brand of horror, and subsequent games only build on that foundation. In addition to the vampiric touch of the titular parasitic species, Metroid Fusion introduces an alien species that subsumes and assimilates any living organism it comes into contact with. This creature — the X Parasite — fuels the events of Fusion and Metroid Dread by taking over the bodies and minds of every creature Samus comes into contact with; after a point, killing anything in Dread reveals only a burst of parasites in its place. The end result is an inherently hostile universe in which no kind of touch is safe, in which the very act of contact or connection can sacrifice one’s own life and self. And it’s against that backdrop that the Screw Attack makes its own twisted kind of sense: a fitting response to a cruel and hostile universe, a tool that allows Samus to flip the script, turn the tables, and destroy with her own touch, to become immune to contact damage by dealing it instead. In the end, Metroid is a horror series with contact at its heart: a work about the impossibility of touch manifested in a realm of parasites and everpresent harm.

***

Nearly four years ago, back when it first came to Netflix, I watched Neon Genesis Evangelion for the first and only time. I had graduated college about a year before and was living with my parents in the Philadelphia suburbs, working a remote job full-time from my childhood bedroom. I didn’t own a car, which limited my day-to-day travel to the small strip of shops at the end of our street and a couple nearby fields. Still, even if I could have driven out, most of my friends — high school, college, and otherwise — lived anywhere from hundreds to thousands of miles away. It was that sense of loneliness and isolation I took into watching Evangelion, and, as I’ve played through most of Metroid over the past two years, those memories have begun creeping back into my mind.

Evangelion, like Metroid, is a work about the existential horror of the thought of human contact: of the painful, lonely ways in which people hold themselves apart, and the even more horrifying things that happen when they don’t. It opens with the hedgehog’s dilemma: a thought experiment that conceptualizes the fear of growing too close to another person, realized in an arc about its main character resisting his entrance to the show’s small, doomed paramilitary community. Its ending, in which its characters face the prospect of “instrumentality” — of all human individuality melting into one single unified consciousness and soul — forms a kind of antipode to Metroid‘s thesis of destruction. The advent of instrumentality in End of Evangelion sees all of humanity melted into a sea of proto-amniotic fluid, the physical and spiritual boundaries that had kept people’s psyches separate torn apart by the actions of the series’ main characters. In doing so, it sees its young protagonists figuratively and literally torn asunder: their bodies weaponized and destroyed in service of those goals. Alongside this mayhem, it paints a stark and lasting image of the ways in which these teenagers separate themselves from a cruel and hostile world, falling into their own individual versions of depression and acting out in ways that only isolate them further. When I finished the show back in 2019, I wrote the following over on the Waypoint forums:

I have had a lot of days, some coincidentally while going through this rewatch, where I just feel throughout my being that my presence is a net negative on the world around me, and that the act of existing is in itself some kind of malicious act I’m perpetrating on the universe. So a show pushing through everything it pushed through to deliver a message of not “you can be happy again” or “you can beat depression” but instead “it is okay to exist” was an immensely meaningful moment.

Evangelion‘s conception of depression is difficult to pin down; like the condition itself, it’s inconsistent and complex, manifesting in different ways as its characters struggle to find their places in a fast-collapsing world. Through it all though, across multiple endings and retcons and chaos, it seemed to return to that message: not about improving or getting better, but simply coming to terms with ones own continued existence. As in Metroid, unfettered contact is in Eva too painted as the ultimate kind of horror: the instrumentality project, driven by grief and fear of loss, creating a world without motion or connection, anodyne and bleak. End of Evangelion sees its male lead, Shinji, try to choke his friend and rival, Asuka, after they emerge separate and whole from the ocean. Then, she reaches up and touches his face, and he breaks down in tears at the gesture of affection. In a direct rejection of the fear of contact that drove the Instrumentality Project, touch in its most violent form is met with unexpected, undeserved kindness. It’s that image that Eva leaves its audience with: a final moment of tenderness and violence, and a strange, grief-stricken repudiation of the horror at the show’s core.

It’s in a similarly violent form of touch that the Screw Attack, and the Metroid universe as a whole, finds its real and lasting horror. In these worlds, at least as they’re shown on-screen, there is no affection to be found: no idyllic home where Samus can live out her days outside the confines of her power suit. Orphaned as a child and raised by an alien race represented almost entirely by their ruins, she spends the first game trawling the remnants of her homeworld and concludes the third game by blowing it to pieces. Every challenge drives her further from any kind of contact — peaking in particularly brutal fashion in Metroid Prime 3, when she’s forced to kill multiple friendly hunters as they’re overtaken by a corrupting, mind-controlling organism. She’s experimented on, genetically manupulated and modified, even injected with metroid DNA to stave off a parasitic infection. In the final moments of Dread, she finally becomes the creature she was once tasked with eradicating, her modified DNA metastasizing into that of an energy-siphoning metroid. And through all this, the series’ thesis remains clear. To survive, Samus must make herself even more hostile than the world around her — she can do nothing but shield herself with current and watch as every living thing she touches explodes in a shower of sparks. And then, she must do it over and over and over again, every time a new mission brings her to the brink of destruction.

The difference between Metroid and Eva‘s diametrically opposed conclusions lie most strikingly in the way both works treat gender, and by extension their attitudes towards femininity and motherhood. Evangelion first locates instrumentality in the bond between mother and child, revealing late that the mechs its teenage protagonists pilot were built from the bodies of their mothers, and that act of piloting those mechs (in a Freudian sense) returns them to a kind of embryonic void. That final scene weighs Asuka, the series’ final girl, with the responsibility of forgiveness, and the role of acknowledging its male lead’s humanity amid a wider world that hurt and maimed them both. The series’ men — Gendo, Kaji, and eventually even Shinji — invariably become the worst versions of themselves. And when it can, the show tasks its female characters — Asuka, Rei, Misato, and others — with initiating their redemption. Despite the range of personalities and roles among its female cast, Evangelion casts femininity as tender, mothering, unconditionally forgiving and accepting of transgression — permanently and irreversibly saddled the responsibility of care.

But in Metroid, the fantasy of the Screw Attack lies in being able reject that responsibility of care. It’s the freedom to ignore the world around you: from how it’s composed, to the dangers it holds, to the ways one might need to bend to find a place within it. Once Samus and the player learn the passageways and warrens of whatever planet they’re exploring, it allows unfettered movement in any and all directions, through any hazard or strange creature that might stand in their way. And to justify it, the Metroid series crafts a universe where touch is itself the ultimate source of horror — where the only response to the hostile, alien swarm is to make yourself untouchable, unambiguously alone. In a piece for Wired in 2017, Laura Hudson wrote that the horror of works like Metroid and the Alien films “is the violence and horror so often faced by women: not only how terrifying it is to face the threat of sexual violation, but how terrifying it can be to bring life into the world, and how terrifying it is every moment after, to love something that much.” The Metroid series works Samus through every version of that terror, facing her with loneliness and loss at every turn. As a child soldier, an executioner, a surrogate mother and the subject of repeated genetic engineering, she routinely faces down horrors so invasive they redefine the very makeup of her cells. The Screw Attack, then, becomes a kind of antidote — a pharmakon, both remedy and poison — and a device by which Metroid‘s gendered, interstellar horror transforms into one of gaming’s strongest power fantasies.

After all, in a universe rife with hostile contact, with survival predicated on the ability to stay solitary and alone, what better way to secure peace than to to make yourself impossible to touch at all?

Your concluding statement reframes Prime 4’s ending in a very interesting way.

LikeLike

Ooh interesting, I haven’t played 4 yet. Should get around to it soon.

LikeLike