There’s a commonality present in most art about cataclysm and catastrophe: a kind of violence that manifests in subtle, yet never subversive ways. Apocalyptic fiction (and post-apocalyptic fiction) thrives on the quest for salvation, on the journey of a set of intrepid warriors or scholars or something in between, hellbent on saving themselves and their world from the fire raining down before their eyes. There’s a conservativeness inherent to these stories, a glaring fear of erasure that masks a subtler fear of any kind of change. Depending on the story, this might be justified. Often though, apocalyptic fiction falls into the rut of railing hopelessly against cataclysm, in the hope that in those final throes someone, somewhere, will see the struggle, and grant mercy.

Video games consistently hew closer to that interpretation than any other form; the only thing that matches the medium’s fascination with apocalyptic settings is its paired infatuation with the violence they (seem to) justify in the name of saving the world. And it makes sense in a roundabout way; games are built to be eternal. Replayable, never-ending, giant worlds to continue existing and exploring even after nothing new remains under the sun. It makes sense that games are afraid of endings.

So what happens when a game presents a world that’s in the midst of ending, and slowly tells you that there’s nothing you can do?

[warning: spoilers ahead for Mobius Games’ Outer Wilds]

Outer Wilds is an independent exploration game that began as a graduate thesis at USC and became, in my view, one of the most extraordinary games I’ve ever played. Not for the sheer beauty of its clockwork worlds and the vastness of its systems and scope, nor for the way it somehow manages to make its core solar system feel both intimidatingly expansive yet explorably small. I finished it about three weeks ago, and I haven’t been able to stop thinking about it because, put simply, it’s a game about being powerless in the face of cataclysm, and accepting that for what it is.

***

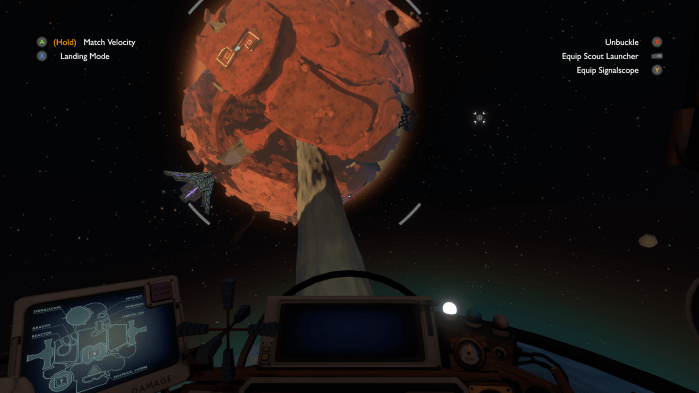

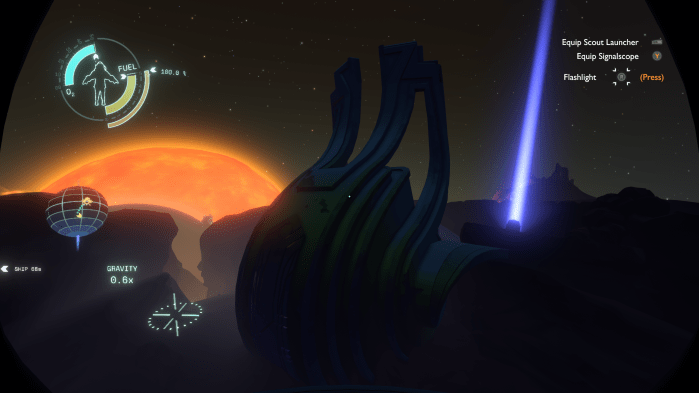

In Outer Wilds, you play as an astronaut at the vanguard of a fledgling space program—a member of an alien species that had developed the means for spaceflight by way of wooden rocketships and rudimentary electronics. The game’s form of space travel is ramshackle and earnest, and, in its inspired, run-down fashion, fully captures the feeling of venturing into the vast unknown with little indication of what may lay there in wait for you. Exploration is your main, and, at least for a while, your only purpose. There are several other planets out there for you to explore, along with a subterranean network of geysers and reservoirs on your own that hold their own secrets. For a few minutes—22, to be exact—the universe lays at your feet.

And then, the sun explodes.

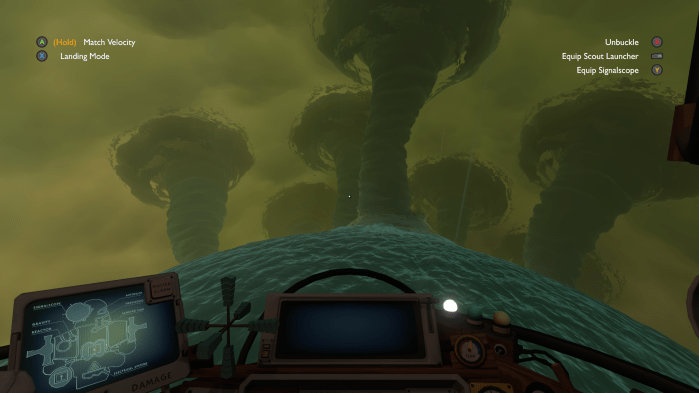

You wake up, as you did at the start of the game, in a clearing beneath your launch pad, gazing up at Giant’s Deep, your solar system’s great oceanic gas giant. Orbiting that dark emerald planet is some kind of station that, as you watch, launches a bright purple speck out into the universe. Then, it fractures.

This kicks off the game’s core mystery, and lends a purpose behind its exploration. Over the course of the following 20-30 hours, you uncover a devastatingly simple history that reveals both the nature of that station and the supernova that follows exactly 22 minutes later. The race that had preceded you—a nomadic, spacefaring civilization called the Nomai—had come to your solar system in an attempt to solve a secret, to trace a hidden signal to… something, that they called the Eye of the Universe. In their minds, this Eye held all knowledge; discovering it would reveal the secrets of physics and science, of the quantum fluctuations that underlie their last greatest mysteries. To the Nomai, you learn that progress came in the form of knowledge. And progress—learning more about the universe and about themselves, solving mysteries for the benefit of their families and their futures—was their raison d’etre.

And after much failure, they devised a way to find it—physically, with a probe that they would launch into the depths of space, again, and again, and again. To power that launch they would create a time loop: a loop that begins with another launch and ends with a supernova of their own design, enough to send all that energy back in time and launch the probe again.

A loop that you and your species are now trapped in, forever.

***

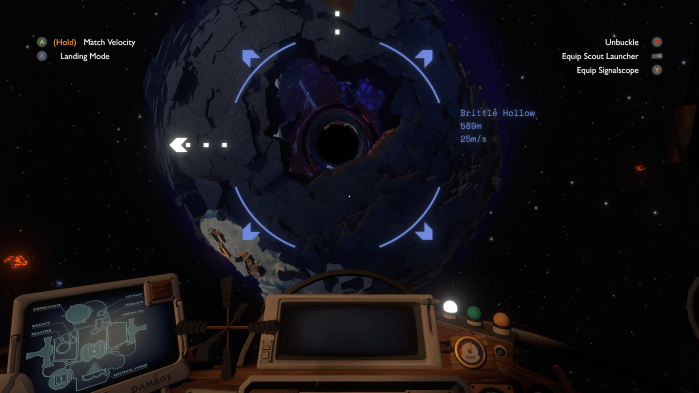

Outer Wilds is infused with a lingering tinge of melancholy, coupled with an overwhelming sense of smallness. Its solar system is vast, and grows only vaster as you explore its strange and stranger depths. One planet holds a black hole in its heart, and over the course of the 22 minute loop, chunks of its brittle surface tumble into that inescapable core. A system of binary planets orbit close to the sun, exchanging the sand that cakes one of its members’ surfaces in a vast, orbiting column. The gas giant you see upon waking features cyclones that, alternate, jet its floating islands up into its atmosphere or propel them down to its electrified core. And a final, corrupted world warps and fogs the space within its reaches, which are filled with massive, ship-eating angler-fish.

All of these systems operate like clockwork, unfazed by your minuscule intrusions. In much the same way the Sun will never respond to your pleas. As you uncover the story of the Nomai, you learn—through implication and observation, through long-forgotten writings and the broken remains of their stations—that because of a lack of foresight and one too many human mistakes, there is no way to stop the progress they tried and, in their time, seemingly failed to set in motion. Millions of years later, their machines blew up your sun. And there’s nothing you can do to stop it.

So instead, Outer Wilds has you finish their quest. It asks you to enter the Eye of the Universe, and to solve the mystery that they never could. Early in the game, you explore your people’s observatory—your museum of air and space, and see a model of a supernova. Its sign reads:

“If a star is massive enough, it will continue to fuse carbon into even heavier elements. Ultimately, the star will collapse under its own gravity and then explode in a violent event called a supernova. Based on Chert’s observations, this will one day be the fate of our own sun.”

When, a lifetime later, you enter the Eye of the Universe, the game brings you back to that space, now dark and floating in some vast netherworld. The future tense in that sign changes, now to simple past.

“At the end of its lifespan, our sun collapsed under its own gravity and then exploded in a violent supernova.”

The end has come. No, it came. And it left.

Then—before your eyes, a new universe begins. One with strange new creatures, new stars, new suns. New life, ready again to explore.

***

There’s a strangeness to growing up under the threat of climate change. I’ll be 24 in a few months, and often it feels like all of us in that range may be crossing the halfway point of lives that will end with floodwaters and wildfires rather than hospice beds. That would, of course, be a mercy compared to the vast majority of the world’s population, especially those already marginalized and exploted by the throes of late capitalism, where the refugee crises of the past few years will look like little more than a late-Friday evening traffic jam. But from a purely selfish standpoint, the anxiety is still always there. I’m at an age where I should at least have a tentative answer to the question of “do you ever want to have kids,” but even trying to answer it leads me down a rabbit hole of irresponsibility. Knowing what we’ve seen will happen twenty, thirty, forty years from now—how can I answer that question? Knowing what’s already happened, even if some kind of sudden, collective action arises in the next, crucial decade, how can I even try? There’s a feeling of smallness that, even on better days, I can never quite see past. That, on the worst days, becomes a kind of hopelessness.

Art about climate change and the cataclysms it may bring also exists in a strange subliminally escapist state. We’re overwhelmed with disaster movies of all shapes and sizes—Randian superhero blockbusters about a world that can only be saved by a chosen few, creature features and kaiju flicks diving into the same kind of post-atom bomb anxiety that fueled Godzilla’s initial creation, post-apocalyptic shows and novels and games depicting a version of the world taken back by nature. None of these pieces come right out and say it—and to its credit, neither does Outer Wilds. But they all feature the same undercurrent of angst, a feeling that the world is coming to an end, and a resulting (usually violence-filled) quest for salvation.

But Outer Wilds doesn’t present cataclysm as an object of rage, or as the driving force behind a noble quest for salvation. In a sense, it hews closer to the historical version of apocalypse—a time of discovery, enlightenment, and rapture. At the same time, through its central loop, it builds a simple and moving allegory for growing up in a world laying in the shadow of cataclysm—for watching the universe come to an end because of things that happened long ago, and for feeling powerless in the face of the past.

In the end, Outer Wilds asks you to accept that, alone, you cannot stop its cataclysm—and, more broadly, to accept the very idea of ending. To understand that there will be an after, that the beauty of the systems you spend so many hours exploring will return in some new and ephemeral way. That the universe is impossibly vast. That yes, they blew up the sun, and there was nothing you could do. But to push forward into the uncertain and the unknown, and understand that something new can still come.

And on a broader scale, that, in the end, the universe is infinitely stranger and more unexpected than you could possibly imagine. And the true privilege of it all, is being there to witness it.

One thought on “In Outer Wilds, They Blew Up the Sun, and There Was Nothing We Could Do”