As 2020 ends, I’ll be dropping posts about video games I played and replayed this year — the ones that most effectively summed up this strange, chaotic trip around the sun. The posts are in no particular order, and can be read in whatever sequence you desire. This piece contains spoilers for Subset Games’ 2018 mech tactics game, Into the Breach.

***

“Giant humanoid mechs aid in tasks civil, commercial, and military. And sometimes you look up to them and think ‘We could have made them look like anything, but we made them look like us.‘”

—Austin Walker, COUNTER/Weight

It was not the first time Abe Isamu had witnessed the end of the world. Sometimes, it came with an explosion — a bomb igniting a subterranean hive, its incandescent eruption piercing the upper atmosphere. Sometimes, it came in gathering darkness, with hordes of insects swarming the surface of the Earth. This is the central tenet of Into the Breach, that, if not for its humans then for its pilots and mechs, the end of the world is coming. If not to their liking, the only option is to go back — to open a rift to another timeline, and try again.

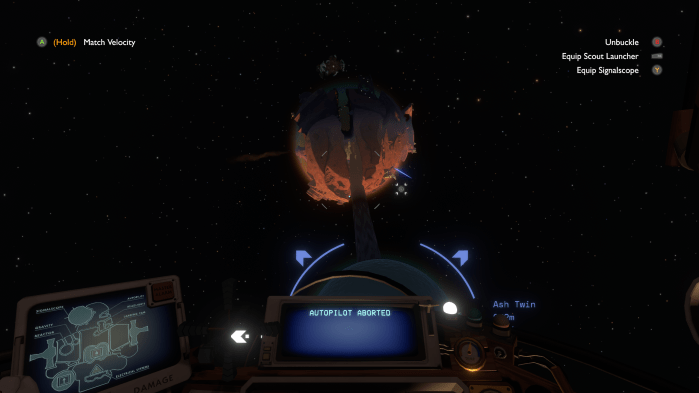

Video games are, as a medium, categorically fascinated with the end of the world. Look back through a few of my posts on this site and you’ll find most of my personal favorites — Death Stranding, Outer Wilds, Hyper Light Drifter, Bastion, SOMA, and way too many posts about The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild. Compared to those games, Into the Breach‘s vision of endings is, in a way, much more abstract. After all, the others operate on a decidedly human scale: Death Stranding and Breath of the Wild cast you a lone hero the midst of a rebuilding, post-societal wilderness; Bastion has your protagonist, The Kid, maintain a last line of defense against apocalypse; Outer Wilds asks you to grapple with the specter of an inescapable demise in a universe far larger than your small, humanoid body can fathom. Into the Breach — with its 8×8 grids becoming a kind of smoking, acid-bathed, cataclysmic chess board — never even shows the people enduring its particular vision of apocalypse. They fill the buildings that speckle its maps, occasionally shouting expressions of fear and terror and awe — all of them dwarfed by the mechs, pilots, and massive, mutated insects doing battle outside their windows.

Yet even though Into the Breach‘s vision of apocalypse shows little of humanity beyond the faces of its pilots, it is — as all mech fiction is — fundamentally a game about bodies. After all, mechs themselves are bodies; extensions of a pilot, tasked with performing a kind of work that they cannot. The mechs built to face down this game’s insect-induced apocalypse are surgical, precise — for all but a few, their damage alone isn’t enough to beat back a wave of Vek, much less an entire hive. Instead, they move, displace, and deform the world around them: flipping these building-sized insects from one side to the other, pushing them across grassland or into environmental hazards like lakes or sinkholes. Because of the game’s design — enemies that reveal their moves at the end of their turn, giving you a chance to eliminate, block, or shift their positions on that chessboard-like grid — some squads even excel at positioning the Vek to take each others’ attacks. Over on Waypoint (now Vice Games), Austin Walker wrote that Into the Breach turned mech combat into a “tactical dance” — and I’ve yet to find a better metaphor for the game’s elegantly-unfolding battles.

So with that in mind, what kind of bodies are these? Dancers? Surgeons? One squad, the fire-immune Flame Behemoths, wins battles by setting the entire map aflame and burning the Vek to ash. Another, the Rusting Hulks, cover the map in storms of electrical smoke — shocking the Vek into submission. Each squad is a set of three — drawn from four potential categories. Most “Prime” mechs — the ones tasked with punching, blasting, or displacing Vek at close range — appear at least somewhat humanoid. Meanwhile, “Brute” mechs appear tank or jetlike, and mostly — like a rook — deal in straight lines. “Ranged” mechs take on a similar attack pattern and a similar, launcher-like, almost insectile appearance, but with missiles that can arc over buildings or other obstacles. And “Science” mechs, the most distant in appearance from human or animal life, pull, push, and reposition Vek as part of that overarching tactical dance.

With that wide variety of bodies comes an equally wide array of abilities — ones that employ fire, lightning, gravity, ice, and other primal forces to beat back waves of these massive insects. And after hours and hours of moving those bodies around these chessboard grids, leveling mountains and razing forests with powers of the kind usually attributed to gods, the game’s subtext begins to emerge. For all its smoke and flames, Into the Breach isn’t really a game about cataclysm itself — it’s about what led us there, and the increasingly invasive, disastrous measures needed to prevent a final slide into extinction.

***

Though there is an Earth outside the core setting of Into the Breach, populated, according to the game’s victory screen, by a only little over half of our world’s current population, the game limits its missions and combat to four islands sequestered by a vast ocean. Each island is owned and managed by a corporation — Archive Inc., R.S.T., Pinnacle Robotics, and Detritus Disposal. And in opposition to the mechs’ surgical incisions and tactical dances, these islands’ CEOs know nothing but mayhem. Archive reemployes 20th century weapons of war with all the finesse of a toddler with a hand grenade; R.S.T. has terraformed their island so precipitously that entire sections of it routinely collapse into the earth; Pinnacle creates and manages “sentient A.I.” that, for the most part, can never tell friend from foe; Detritus disposes of waste with vats and lakes of trademarked A.C.I.D. that eat away at any unit unlucky enough to wade through them. At their best, these blunt, clumsy forces can be a small assistance in a series of missions. At worst, they can actively hinder your chances of success, endangering mechs, pilots, and even their own islands’ citizens.

That these are corporate islands run by “CEOs” isn’t some small detail — after all, like most of the games I’ve written about elsewhere on Sunset Over Ithaca, Into the Breach‘s cataclsym is a thinly veiled metaphor for ecological collapse. The Vek themselves are a natural threat: insects born either of intentional human meddling or accidents on a grand industrial scale. Natural disasters wrack these islands, from tidal waves that sink huge swathes of land to blizzards that encase entire cities in ice. Naturally, the corporatized response to threats on such a scale is to engage a new kind of mutually-assured destruction — to terraform an island into a state of permanent drought, or to cover a vast landscape in corrupting, eroding acid. Rather than solve the problem of environmental catastrophe at its source, the game’s vision of the future locks us in a death spiral. To stop the Vek from inheriting the Earth, we must destroy it.

With that in mind, Into the Breach‘s mechs become the natural escalation of that response to cataclysm. In other words, if we cannot exterminate the Vek by reshaping the Earth, we must instead reshape ourselves. Give ourselves bodies the size of skyscrapers that can shield people and structures from all manner of enemy attacks. Bodies with powers once reserved for Thor or Wadjet or Gaia, that shake the earth and inspire awestruck exclamations every time they land. Recreate ourselves, physically, as gods.

There’s only one small issue with this plan, of course. Unlike gods, we cannot make ourselves immortal. Unlike acid vats or bombing runs or tidal waves, mechs have bodies, and thus, they can die. Depleting a mech’s health pool in Into the Breach results in two direct outcomes: the pilot, if one is present, dies with them, and the body goes dark and dorment — collapsed, where it will remain for the rest of that mission. A dead mech persists in this world like bodies do; if it dies above a spawn point, that spawn point will remain blocked; if it dies in the way of an attack, its corpse of metal and glass will receive every ounce of it.

And with that image, Into the Breach becomes a game about sacrifice. At the end of each run, whether victorious or failed, pilots can open a rift and shift to a new timeline — a new chance to save an Earth from ruin. Mechs, on the other hand, cannot. Even in victory, they finish dead, shriveled and powerless on the ground in the Vek’s subterranean hive. In this final attempt to save ourselves from the consequences of centuries of environmental destruction, we’ve remade ourselves as gods. But even these new gods can’t seem to stop their bodies from dying.

***

In a way, Into the Breach mirrors what I wrote about Outer Wilds, my 2019 Game of the Year. Both are games about cataclysm that not only seems, but is inescapable. And both reveal this inescapability through travellers and time loops — engineered by people who hadn’t quite, in the words of Jurassic Park‘s Ian Malcolm, “stopped to think if they should.” But while Outer Wilds melds that inevitability with hope — that there will be an after, even if not for us, as long as we can escape our own frenzied cycles — Into the Breach is a more morose parable. Because Into the Breach offers no escape from that cycle, not to its characters — the pilots — nor to the player commanding them. Loop after loop, we return to minutely different versions of the same four islands, ready to face a slightly remixed array of the same set of enemies; once more, we’re powerless to achieve anything beyond that doomed, endlessly cyclical future. Unlike in Outer Wilds, no one in this world has accepted the inevitability of its ending; they still do war with it, to the point of recreating themselves as gods.

And that brings me back to Abe Isamu.

While most of Into the Breach‘s pilots are procedurally generated, there is a special set of “named” travelers that you might encounter when opening escape pods from other timelines. Abe Isamu is one of those pilots, one of a special group of non-randomized characters with one special, helpful attribute they lend to whatever mech they happen to pilot. Abe’s is rather simple, yet incredibly powerful: his mechs receive armor, which shaves one point of damage off of any attack they endure. He’s also a unrepentant militaristic fascist — constantly dropping voicelines about strength, weakness, victory, and cowardice. And in the midst of battle, he makes whatever body he’s assumed just a little stronger than everyone else — able to take beating after beating from city-sized bugs sometimes without even taking any damage.

This is Into the Breach‘s subtext — its special pilots, or “travelers” as the game calls them, have seen timeline after timeline laid to waste by either Vek or humanity itself. And with that, the mechs they pilot respond to their personas and beliefs by literally transforming themselves in their image. Abe gives his assumed bodies armor; other pilots can grant their mechs a shield, revised attacks, additional movement, even flight. That is the nature of this death spiral, of the mutually assured destruction humanity and the Earth itself lock into: human bodies recreated and warped and transformed without choice, in the same way the Vek themselves have been transformed by the world around them. Metal so entwined with human destiny that it evolves, like flesh and blood.

And fittingly, once each achievement has been cleared, the game unlocks a ninth, hidden group of mechs: the “Secret Squad” — cyborg Vek, pilotless, reengineered with human ingenuity for that same eternal mission. Designed for sacrifice, the mechs of the Secret Squad survive death with just a small loss of XP — and, at their fullest, come to mirror the Vek’s most powerful variants. But if they succeed, they die just like every other mech; incinerated by an explosion in the center of the Vek’s volcanic hive. Above all else, the Secret Squad provides Into the Breach a simple, incisive epilogue: in our final attempt to establish dominion over nature, we remake not only our own bodies, but the agents of collapse themselves, as subservient gods.

***

The Earth was once home to giant insects — in the Paleozoic Era, a higher concentration of oxygen in the atmosphere allowed bugs to grow to much larger sizes. Imagine dragonflies the size of hawks, and spiders the size of monkeys. It was nature itself that ended that era — when climates changed and birds, with the specter of extinction looming, birds evolved from dinosaurs.

This is how nature works — it spins itself an an ever-lengthening helix, changes in evolution balanced by new developments. That’s the process that we’ve disrupted, with technology and industry and the progression of an ideology, in capitalism, that assumes infinite resources will power infinite growth. And in a year like 2020 — where wildfires have blackened the skies above entire continents and a zoonotic virus has killed, as of the year’s end, almost 1.8 million people — narratives of ecological cataclysm feel both more urgent and more desperate than ever. We may never need to build giant robots to defend ourselves, but the need to build new bodies has never been less far-fetched. Not out of idealism, or a desire to make ourselves better, but as a last ditch effort to survive a cataclysm decades of policy and industry and collective choice has brought to pass. To endure newer and sharper climates, famines, droughts, plagues and pandemics with each passing decade.

Are we there yet, beyond the point of no return, where survival means a descent into mutually assured destruction? I hope not. But with another few years of emissions and pollution and general destruction, we’re well on our way.

And if we’re already there?

I guess it’s time to open a breach.