As 2020 ends, I’ll be dropping posts about video games I played and replayed this year — the ones that most effectively summed up this strange, chaotic trip around the sun. The posts are in no particular order, and can be read in whatever sequence you desire. This post contains spoilers for Black Mesa and a 22 year-old game called Half-Life.

I don’t expect to see Black Mesa — Crowbar Collective’s long-awaited remake of Valve’s original Half-Life — on many GOTY lists. There was a significant portion of the year in which I didn’t expect it to top mine. More so, before the release of Hades and Miles Morales in the last few months, I was a little worried about that prospect. Up to that point, Black Mesa hadn’t had a lot of competition for the spot I’d tentatively penciled it into at the top. Because I’d spent much of this strange, destructive year replaying old gems or chowing down on bite-sized Apple Arcade offerings or tending a tarantula-infested island — none of which had moved me in the same inexplicable way — it seemed to be winning by default. That’s never a comfortable position to find yourself it.

But in the end, the competition it eventually received was what truly cemented its spot — and, more so, made me realize that being inexplicably moved by a game might just be what a Game of the Year title is for. Hades is a brilliant game, with intricate writing and a narrative that captured my imagination for weeks of my life. Miles Morales is a sublime, beautifully-plotted excursion through one of the best open worlds I’ve ever experienced — made even better by my familiarity with its predecsssor. But when it came time to really sit down and pick, neither of them really came close.

And for me, that comes down to the phrasing. There’s a reason that the phrase isn’t “Best Game of the Year” — an adjective like best (or a more exact noun, like “Best Picture” or “Best Record”) would narrow the idea at play. But “Game of the Year” is loose and open to interpretation; it signals that this thing meant something to someone, in some core, primeval way. And that’s what Black Mesa did — it meant something to me. It realized, in elegant, unmistakable (and yet perhaps not even intentional terms), a core theme behind the game that made me love video games.

Or, in other words, it gave Half-Life an ending it deserves.

***

In Half-Life, the “border world,” Xen, is a boring, frustrating, disappointingly clumsy piece of work; after the seismic sequence of battles and chases that make up the first 75% of that game, the player is yanked from a series of detailed levels in the vast, warren-like Black Mesa Research Facility and into what feels like a Mario 64 test stage. Floating platforms orbit other, larger platforms, all painted in the same ugly shade of greenish-grey. Surrounding them — above, below, in every single direction — you’ll find a cloudy, nebulous skybox that looks like someone searched “outer space” in a collection of a 90s desktop backgrounds. Once a shooter with light puzzle elements, Half-Life then becomes an awkward, first-person, 3D platformer — a trend that persists through about two hours of increasingly confusing and labyrinthine levels, in which the way forward always looks exactly like everything else: drab, lifeless, and greenish grey.

Xen was supposed to be a climactic experience — the end goal of Gordon Freeman’s increasingly harried quest through the research center, the place in which all of Half-Life‘s thorniest secrets would be answered. Instead, what should have been a strange, ethereal world of alien life feels like almost nothing at all.

That was, in short, Half-Life‘s biggest failure — mechanically, narratively, and systemically. But, as you can probably guess from my preamble, it’s Black Mesa‘s greatest success.

***

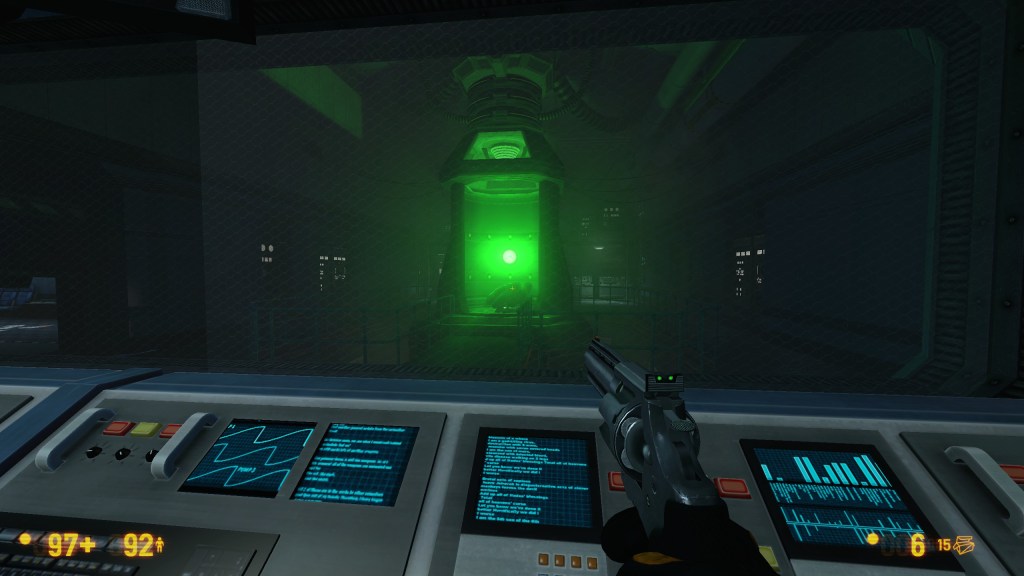

Black Mesa‘s vision of Xen is a wonder of the kind that only games have ever made me feel. From the moment I entered — having dove through a collapsing teleporter as alien forces coalesced around me — I felt utterly lost, alone, and alive. The game wisely opens the level in the darkness of a cave, allowing you to get your bearings in the comfort of shadows. Then, it guides you from the teleporter’s exit site to the opening in the screenshot above — a precipice above a vast, glowing abyss filled with asteroids and glowing crystals and beautifully strange raylike creatures that swoop across your field of view. The only thing I can compare that feeling to is, put simply, the clifftop from Breath of the Wild — but even that feels inadequate. The entrance to Xen was singular, something I reloaded multiple times to experience over and over again. In that moment, it delivered on Half-Life‘s original promise of losing oneself, long after that game had begun accumulating dust.

But the best trick Black Mesa pulls — the real reason it maintained its foothold in my brain throughout the chaos of 2020 — was not its entrance. It was what came after: the way it found meaning in the incompatibility between its own wonders, and the verbs that video games still cling to twenty-two years after Half-Life‘s release.

***

Shortly after that reveal — the moment Gordon Freeman first sets foot outside his own world — Black Mesa becomes what, in a sense, Half-Life always kind of was: a survival horror game. Except, rather than the kind of survival horror that the genre thrives on, with gloomy locales and dark, abandoned buildings and unseen monsters shuffling across rusty floors, Black Mesa attempts the opposite. It creates an expanse of pure wonder — a place that truly looks and feels and sounds like another world, filled to the brim with beautiful foliage and strange creatures and impossible, alien physics — and it places you as an invader in its midst. Half-Life had always set Black Mesa’s researchers and scientists as its real villains: a vanguard of colonizers exploring a world unknown to the rest of humankind, kidnapping its native fauna and subjecting them to inhumane experiments (the subject of an earlier chapter appopriately titled Questionable Ethics). But the payoff in the original game was mostly nonexistent: a few bodies left on those drab platforms, more resource drops for Gordon’s continued survival than actual actors in a narrative script.

Black Mesa, on the other hand, leans fully into those narrative beats — establishing Antarctic-style research bases that Gordon must work his way through on his way to the game’s inevitable conclusion. In those bases, he comes across both copious research scrawled on whiteboards — clearly the product of years of illicit work — and the remains of Black Mesa scientists. The lucky ones are simply dead. The unlucky have been zombified by Half-Life‘s most iconic creature: the headcrab.

These enemies shouldn’t be novel — zombies are a fixture in Half-Life and Black Mesa, as well as every other game in the Half-Life universe. But these zombies have a unique feature; like Gordon, they all wear Black Mesa’s HEV Suit. And so, whenever you succesfully injure or kill an lunging zombie, you hear the same warning lines and the same high-pitched whine that plays every time Gordon himself approaches death throughout the game. The effect is effortlessly eerie: a reminder both of what happened here, of complicity in the atrocities carried out on Xen‘s alien wildlife, and of how exactly that strange, alien world has chosen to fight back.

In that idea lies the crux of Black Mesa‘s significance — both as a remake of an iconic title and as its own unique and uniquely flawed piece of art. As a first-person shooter, Half-Life only really had one mode of play: combat. There was some puzzle-solving here and there, some physics thrown in to signal Gordon’s MIT pedigree, but the game was spent chasing or being chased, shooting or being shot. (Fitting for a game with the tagline: Run. Think. Shoot. Live.) And for better or worse, Black Mesa is the same: it’s kill or be killed, first by aliens yanked to your world by a cosmic-scale mistake, and then by aliens defending their home from you, an invader trying to stuff all the evils back into Pandora’s Box. And faced with the wonder of Xen — this strangely beautiful alien world filled with color and vibrancy and life, there’s something innately disappointing about that. As I made my way through lakes and rivers, up rocky crags and over huge abyssal gaps, I wanted another way to interact with this world. Another game, even, that would give me something other to do than invade and kill its wildlife.

But in the end, Black Mesa draws power from that limitation; it clarifies and rewires Half-Life‘s undercooked tale of invasion and colonization — one that continues with humanity itself colonized by an unimaginable cosmic empire. In that sense, Gordon arriving to Xen with his arsenal of weapons and no clue what awaits him feels fitting; in 2020, it should be clearer than ever that the mistakes, evils, and constraints of the past always ripple forward into the present and future. It’s damning in a way just utterly perfect for a year like this, a world like this, and — with Half-Life‘s clearly-intentioned Americanness in mind — a county like this. To be surrounded by beauty, and given the choice only to destroy. To be told that another world is possible, only to see it burned beneath your feet. To be returned to the past and shown, with clear eyes, what had always lurked below the surface.

If just for that moment alone, I can’t imagine calling anything else my Game of the Year.