[This list contains light spoilers for the Metroid series overall, including boss appearances, upgrades, and plot points in each game. If you’re worried, only read entries for the games you’ve played. All screenshots are either my own captures or were sourced from YouTube longplays; any videos used as sources will be linked via the images themselves.]

About a year and a half ago, after the announcement of Metroid Dread, I gave myself a mission — to finally follow through on a longstanding fascination and play the entire Metroid series from beginning to end. Along the way, I’ve catalogued the journey on a thread on the Waypoint forums, and collected some of those posts here as mini-essays (and for the purpose of the project, please consider this ranking and retrospective as a collection of the others). And while it took a bit longer than I’d anticipated, I’ve finally played them all.

Now, for more critical thoughts on my journey and the series as a whole, check out my essay about contact damage, the screw attack, and way the series finds horror in touch. But if you’re here for something a bit simpler, less formal, maybe just for fun, strap in for my tiered ranking of every Metroid game — from the ones I struggled to make it through to the ones I wish I could experience for the first time over and over again.

***

TIER 6 — THE SATELLITES

There are, of course, a few Metroid games that are such outliers to the rest of the series that it doesn’t feel fair to include them in the rankings proper. So this is the tier for them: unranked and unbothered, orbiting the series like satellites. At worst easily forgettable, at best good for some brief moments of fun.

NR: Metroid Prime Pinball (DS, 2005)

In a word: surprising! Who knew how easily and well the mechanics of Metroid Prime would map onto a pinball game. The stages manage to translate a surprising amount of the main game’s atmosphere, enemies, and tasks into the simple mechanics of a virtual pinball table, and there was enough variety to keep runs fun and interesting even as I grew familiar with each table’s mechanics. In a way, it does make sense — pinball, like Metroid, is a game about practiced traversal: of learning to manage a particular space over and over again until it becomes almost second nature. Metroid Prime Pinball finds something rewarding in that similarity, and generates a game as worth playing as it is difficult to find.

NR: Metroid Prime Hunters (DS, 2006)

In a word: awkward. Hunters is exceedingly hard to find (or, at least, usually prohibitively expensive) in its original DS cart form, but it’s even harder to actually play without its original console’s touchscreen and form factor. I played a bit of it on my Steam Deck via Retroarch, which let me attempt it on several different DS emulators, but even with all the jury-rigging I tried, it never felt comfortable to play.

From what I did play, though, Hunters seems like a potentially fun deathmatch multiplayer game with a dull and repetitive singlplayer campaign. The first hour or so consisted of cycling through a lot of similar corridors and copy-pasted enemy swarms, with a facsimile of the Prime games’ mechanics but none of the traversal challenges or environmental puzzles that made elements like scanning or the first-person view interesting. It’s a curiosity — not a bad one at that — but one that, like many multiplayer games from older eras, really just no longer exists in the form for which it was designed.

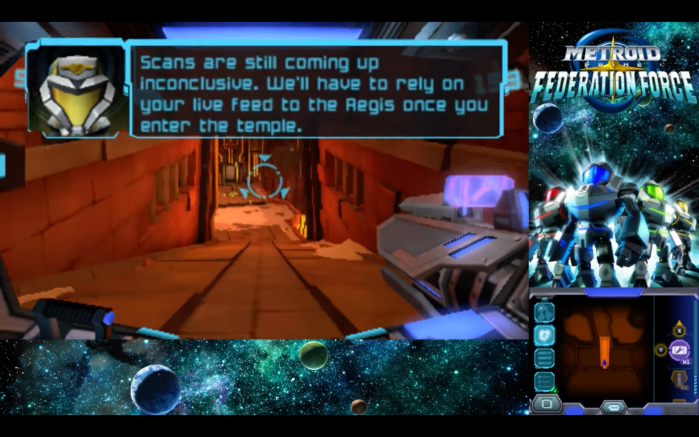

NR: Metroid Prime: Federation Force (3DS, 2016)

In a word: …inoffensive? I enjoyed the brief time I spent with Federation Force, enough to feel like its reception was more due to the circumstances of its launch than the game itself. It’s not much of a Metroid game, and it’s understandable why in 2016 that was seen as an affront. What it is, instead, is a mildly interesting co-op shooter set on some planets that seem like facsimiles of Prime mainstays like Phendrana, Magmoor, and the Bryyo. It integrates some customization systems that, in a true co-op environment, would give it a somewhat class-based feel and a sense of different roles for different players. (Some have called it a heavily simplified Monster Hunter-like, and I think that’s an accurate comparison). Its missions are short and workmanlike, with easy objectives and some minor environmental puzzles reminiscent of the series that inspired it, and a control scheme oriented around the 3DS’s gyro capabilities that felt surprisingly solid to handle. Like Hunters and its multiplayer mode that died with the DS, it would be exceedingly unlikely to find Federation Force in its optimal form six years after its release. But if you could gather enough friends to make it worthwhile, it could be a fun way to spend a few lazy summer afternoons.

And that’s it for the unranked spin-offs and interstitial entries! Let’s get to the main event!

***

TIER 5 — SPACE JUNK

While the two games in this tier are likely unsurprising, their order here might be a bit more controversial. But, in both cases, these are the series’ interstellar dust: one so gloomy and unimportant it’s barely worth playing, and the other such a misfire it managed to turn a premise rife with potential into an agonizing, misogynistic slog.

#12: Metroid Prime 2: Echoes (GCN, 2004)

In a word: inconsequential. I don’t think Echoes is a terrible game, or one that’s not particularly worth giving a try, but it’s the one game on this list I’ve soured on more and more as I’ve gotten farther from the experience of playing it. The main reason, in short, is that it feels utterly meaningless in context with the series as a whole. Nothing of consequence happens in Echoes. The role Dark Samus plays in its plot is virtually the same one she plays in Corruption — a vastly better and more interesting game — and the rest of the game is a mostly plotless rehash of the first Prime game’s ideas wrapped in the drab, dull, and boring aesthetic trappings of a mid-2000s survival horror shooter.

That’s not to say Echoes has no positives — it’s atmospheric and moody and does a good job of capturing the feeling of isolation and loneliness that characterizes Metroid at its best. It makes good use of Samus’s abilities in constructing some memorable environmental puzzles, and its art direction does lend the dual worlds of Aether a sense of post-apocalyptic loss. Its final level, the Sanctuary Fortress, is great swing at a kind of cyberpunk-ish science-fiction that the series rarely attempts. But the rest of Echoes is a grey/brown wasteland bogged down by a kind of game-y feeling that’s absent from much of the series’ best entries, and its bosses — with the exception of the Sanctuary Fortress’s main guardian, Quadraxis — are an agonizing slog, by far the series’ worst. And its final hours are particularly damning: a tedious fetch quest for the Sky Temple keys that plays like a hollow, uninteresting reskin of the first game’s artifact hunt and one of the most bullshit final boss fights I’ve ever experienced in an action game. There are ideas here, and occasionally they shine, but far more often they misfire like an overloaded musket and leave nothing but a pointless slog in their wake.

#11: Metroid: Other M (Wii, 2010)

In a word: wasted. Other M was not without potential, and that potential is partially why it’s not dead last on this list. There’s a skeleton to this game that, if competently fleshed out, could have supported a classic, and once in a long, long while, it breaks through.

Most of that potential is wrapped up in its setting. The Bottle Ship is the best part of Other M — an eerie, lonely space station that can twist and refract its own internal reality in spookily impactful ways. Many of the station’s rooms present seemingly endless environments: hills and forests that roll into the distance, or icy caverns that seem to twist and worm into the bowels of some vast planet. But, when Samus interacts with a terminal (usually at the end of some mild platforming or puzzle), it reveals that illusion of distance as a projection on the station’s dull, metallic walls. It’s a neat trick: one that seeds a lasting distrust of the reality on display and generates a sense of malice behind the ship’s shifting facades.

Moreover, the later reveals about the station’s history actually create some payoff for that feeling. Nominally a research vessel, the Bottle Ship was mainly used to develop living bioweapons from the detritus the Galactic Federation scraped off Samus’s power suit. Those include clones and recreactions of Samus’s worst horrors — like the Metroid Queen, Mother Brain, and Ridley, whose introduction and subsequent battle gives the game one real moment of emotion (and maybe even the best of his many combat themes). There’s a version of Other M made in the vein of Grant Morrison’s Arkham Asylum: A Serious House on Serious Earth — an iconic Batman graphic novel, steeped in character study and psychological horror, that sees its titular superhero descend into a madhouse full of his most iconic villains. This version could have explored Samus’s reaction to all the horrors of her past and paid off the series’ potential for alienness and isolation.

But Other M is not that game. It’s a horribly written, staged, and voice-acted piece of schlock that recasts Samus as a headstrong teenager with daddy issues — a characterization that both clashes with other entries in the series and fails to execute on its own attempted merits. There could have still been something interesting in the story of a teenage soldier bonding with a cold, controlling father figure: the effects that had on her psyche and her life. But Other M‘s writing is too concerned with shallow gendered stereotypes to do even that. Enough has been written about the game’s view of Samus that I don’t feel the need to rehash it, but I think its most misogynistic moment actually comes in relation to the android clone of Mother Brain, who is implied to have developed a soul purely because, via the recreated metroids, she had mothered a batch of surrogate children. That’s the root of Other M‘s misogyny: an attitude toward its female characters that sees womanhood as synonymous with motherhood (and, equivalently for its male characters, maleness with fatherhood). That’s not the only flaw in its writing — like how, bafflingly, it sets up a late game area filled with intrigue and mystery and then never even lets the player enter it —but it’s the most overbearing one. Other M tried to be cinematic, narratively weighty, a serious story for serious people, and it failed on almost every front.

(Which, I guess, is just what Nintendo deserved for asking the developers of Dead or Alive: Xtreme Beach Volleyball to make a Metroid game.)

***

TIER 4 — THE WANDERING PLANET

Metroid is in many ways an odd series, even for the remake-happy world of video games, populated with nearly as many remasters and reimaginings as it is original entries. Playing through the full series, especially in quick succession, meant engaging with multiple iterations on the same ideas — and, in doing so, seeing exactly how their differences in approach changed the underlying feelings of that story. This tier contains a single entry, and is likely where I diverge the most from public opinion on the series.

#10: Metroid: Zero Mission (GBA, 2004)

In a word: hollow. I understand why Zero Mission is generally beloved; for many, it was their entry into the series, and it’s a friendlier, more modernized, technically competent and pleasant-feeling take on a harsh and unforgiving original. It also draws much of its ideas and inspiration from Super Metroid — the series’ most widely acclaimed and influential entry — and provides a suitable facsimile of that game’s approach to world design, combat, atmosphere, and storytelling.

But playing all these games so close together left Zero Mission in a compromised position: both lacking the elements of the original Metroid that, as you’ll see further up this list, I found memorable and compelling, yet still overall inferior to Super Metroid‘s vaster, more textured, more interesing version of this world. Every Metroid game has a linear, intended path: one with which, absent sequence breaks, players will typically find themselves in step. But none of them telegraph that critical path as openly as Zero Mission — a game that turns the harsh, oppressive, alien, and isolating style of its predecessors into a cramped, brightly-lit shooting gallery. I came to Metroid for its unique mix of atmospheric sci-fi horror, for the hostility of its worlds and the intricacy of often hostile zones. Zero Mission‘s inspirations both took their own approaches to those aesthetic goals, but in trying to split the difference between them, it loses almost everything that made them both unique. In the end, the game feels like just a husk: the smoldering ember of a pair of stronger, more intricate creative works, giving off just enough light to keep itself from fully winking out.

***

TIER 3 – THE METROID NEBULA

In the middle of this list lies the series’ breeding grounds for new ideas: the nebula from which its strongest entries and most interesting concepts grew. All these games are flawed in their own idiosyncratic ways, but those flaws feel driven by ambition: by creative new ideas or new approaches to the series’ formula that, while often grating or frustrating, paved the way for better work to come.

#9: AM2R (PC, 2016)

In a word: familiar. In many ways, AM2R follows the same overall template as Zero Mission: taking one of the series’ early entries — a rough-around-the-edges experience made for a heavily limited console — and remaking it in the style of Metroid‘s most beloved and influential game. Still, while Zero Mission‘s end-result felt like an oversimplification of both its inspirations, AM2R inserted just enough of its own ideas to loft it a little higher on this list: a polished, occasionally sublime fangame that deserves consideration with the Metroid series’ official canon.

AM2R‘s main divergence with the game it reimagines comes largely in its approach to its world’s geography. The underground warren of Metroid II was arid, harsh and barren — a non-Euclidian labyrinth that twisted back and forth on itself, rendering the task of mapmaking impossible on a one-to-one scale. But, like every subsequent entry in the series, AM2R makes an in-game map central to its feeling of progression, and as a result forces a reconsideration of SR388’s internal logic. The result here is a set of discrete areas and environments that all feel noticeably distinct, often in ways that indicate a long-forgotten function. The names of AM2R‘s regions seem almost archeologically determined — a Hydro Station, a Research Site, a Mining Facility, a Nest — lending a sense of function, meaning, and intention to discrete slices of its complex of passageways and tunnels. Moreover, most areas engage with a kind of core environmental puzzle: a switch to be turned on, a generator to be activated, a set of pipes to be filled with coursing water. It even incorporates some aspects of the Prime games: an automatic scanning function that provides ecological information and the logs of deceased soldiers, and that generally gives the world a sense of interactability that the SR388 of its original wholly (and intentionally) rejected. Like Zero Mission, it loses a little luster in comparison to the series’ more interesting games, but there’s enough in AM2R to give it its own identity and feeling — and, at the very least, to make it a crowning achievement for the kinds of fangames that aspire to mentioned in the same breath as the series that inspire them.

#8: Metroid II: Return of Samus (GB, 1991)

In a word: hostile. Metroid II, by virtue of its place on the original Game Boy, remains in some ways the series’ most limited entry. Despite a slight increase in computing power, its development team had to grapple with a lack of color — something the first Metroid used liberally in both artistic and gameplay-specific ways — as well as the restrictions to size and scale forced by the Game Boy’s 144p screen. In response, Nintendo’s most experienced team embraced a kind of unified simplicity of purpose and aesthetic the series would never quite reach for again: diagramming a world and a quest singular in their sense of hostility and brutality. Metroid II, in short, is a game about extermination: about Samus entering the lair of a species that, at this point, seems like a naturally-occurring horror of the universe, and destroying every last remnant of its existence. Unlike in its remakes, here she does little else along the way — finding upgrades (and a bevy of missile tanks) as part of her single-minded quest and killing everything she sees along the way. And the metroids, of course, put up quite a fight, demonstrating simple species bonds and instincts for survival, like when a much more developed survivor emerges to fight Samus at the site of a recent hatchling’s slaughter. What Metroid II lacks in the creature comforts and quality-of-life features of more modern games, it makes up for in its commitment to the elegant brutality of its core project: one fraught with ideas of environmental damage and devastation, and one that clearly birthed the later games’ concern and fascination with the nature, roles, and alien sociality of the parasitic species at their core.

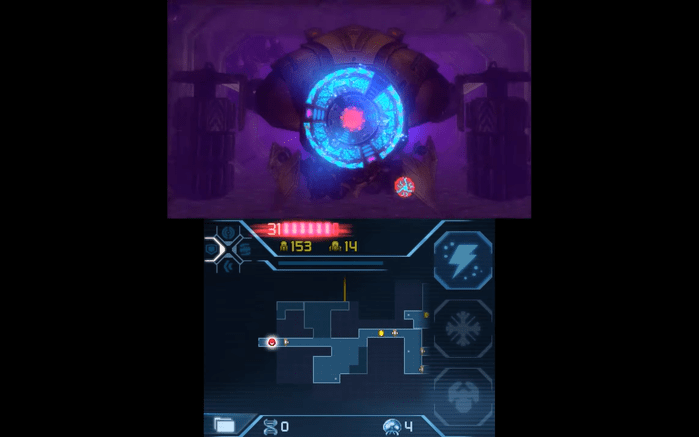

#7: Metroid: Samus Returns (3DS, 2017)

In a word: contrastive. Samus Returns was my first Metroid game, an introduction to the series at a time when it seemed all but dead and gone. Back in 2017, I found the game to be a tight, well-paced, fun to navigate thrill-ride through an immersive and imposing world. Returning to it now, as the final entry in this nearly two-year Metroid playthrough, it plays like a strange amalgamation of everything that came before it, remaking Metroid II with the context of the stories that would follow but losing some of that game’s atmosphere and tone along the way. First, gone is much of the ecological subtext that lurked beneath the original game’s narrative and art direction. Before, the planet’s sea of progress-impeding acid seemed to shift and drain as a natural, inherently ecological response to the metroids’ absence, signaled with an earthquake that shook the Game Boy’s monochrome screen. Now, Samus empties it manually — injecting into Chozo consoles and machines the very metroid DNA that would eventually merge with her own cells. SR388, once an arid wasteland, now plays host to swathes of ancient ruins, the remains of a Chozo mining operation, a genetics lab and terraforming projects, all evidence of past history and life. In line with where the series would develop after Super, Samus Returns transforms the plot of Metroid II from a story about ecology to one about technological malfesiance and decline: one that matches with the themes of Fusion, the Primes, and later Dread, but that shifts the series farther from the isolation that defined its earliest moments.

On the mechanical side, Samus Returns plays like a patchwork conglomeration of all the series’ many pieces — iterating and experimenting but never quite rising to become more than the sum of its parts. Its platforming and sense of movement match up with the feel of the series’ older 2D entries, but come paired with twitchier combat and a less dodgeable, avoidable set of hostile fauna. The game’s main addition, a melee counter move that Samus sweeps upward while standing still, can lead to easy kills but tends to slow the game’s momentum, turning what could have been a fast, kinetic action game into a sometimes halting, jagged slog. Meanwhile, the cornucopia of switchable weapons, beams, and upgrades, as well as the gauge-based Aeion abilities, feel inspired heavily by Prime — and like the Prime games, Samus Returns occasionally finds itself in moments where its controls become opaque, when switching between the plasma beam and grapple beam and super missiles and beam burst feel more complicated than the enemies and fights themselves. Its bosses run a gamut of different feels and vibes, from the Diggernaut — a puzzle-oriented fight also reminiscent of the Prime games — to Proteus Ridley — an extremely simple battle based entirely around careful, practiced dodging, a precursor to the kinds of boss fights that would dominate Metroid Dread. Ridley’s reappearance too diverges from the first game’s strangely hopeful and cathartic ending; instead of simply rising from the earth into the stars, Samus and the hatchling engage in a rough and hectic battle before blasting off into the cosmos. In that, I think, is a microcosm of Samus Returns‘ often twinned strengths and weaknesses. While it jettisons the somber, contemplative moments that its precursor occasionally found, its combination of old and new ideas gave the series a necessary rebirth: a sometimes-clunky, sometimes-sublime prototype for a game much higher on this list.

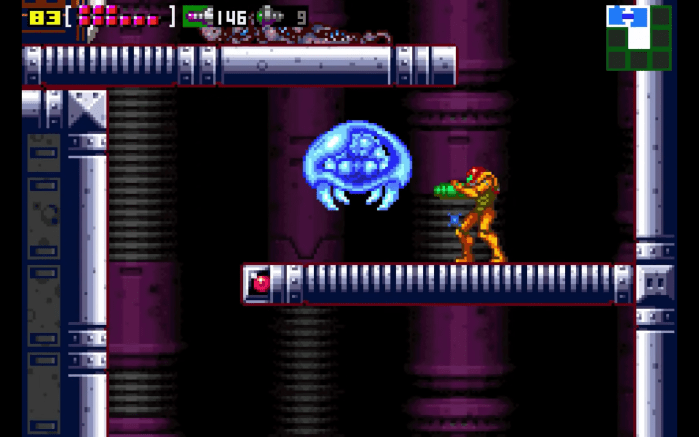

#6: Metroid Fusion (GBA, 2002)

In a word: frenetic. Every Metroid game is linear. Fusion is just the least concerned with pretending that it’s not.

Let me qualify what may be an incendiary statement. Save the first, every Metroid game contains a core, intended pathway through its world — an order to its levels, abilities, and bosses, guided by its environment design and the placement of its upgrades. And while most of the series provides built-in opportunities for playing out-of-order, the allure of sequence-breaking lies specifically in its unintendedness: in the feeling of shattering the game’s rules, of subverting expectations and performing a kind of magic trick on an unsuspecting world. Fusion contains little opportunity for sequence-breaking (so little that it took a decade and a half for its first to be discovered), but, for most of us, its sense of linearity comes from its frenetic, breakneck pace: the way it shuttles its players between the sectors of a claustrophobic space station with unrelenting speed, never leaving the next objective unspoken or unmarked. Fusion is fast, easily the fastest Metroid game — a rollercoaster racing through a colorful yet cramped and hostile world, every moment punctuated by the threats around the corner. On one hand, this creates a driving sense of pace: a powerful momentum that sustains the game’s narrative and horror from opening to close. On the other, it clashes with the kind of exploration and creeping sense of mastery that often characterizes the series at its best. My Fusion run has easily the lowest item clear rate of any of my Metroid saves (45%, below even the 49% I cleared in Other M), and by the time I found the Screw Attack, the main accelerant to travel between the station’s sectors, every ounce of the game’s narrative momentum was propeling me towards its final encounter.

Meanwhile, from a narrative and aesthetic angle, Fusion presents a better, more interesting version of the setting that Other M tried to hard to mimic. For Samus, the B.S.L. research station quickly becomes a menacing, illusive house of horrors, filled with body-possessing parasites and experiments gone-wrong, its passages and tunnels stalked by a doppelganger in the full version of her Power Suit. Samus begins the game having just survived an infection, her body and her armor irreparably altered by the corruption of the X Parasites and the metroid-derived vaccine that eventually saved her life. Those same parasites transformed the detritus of her suit into a unique kind of monster: a dead-eyed copy of herself that hunts her relentlessly (well, in theory) through the station’s labyrinth. But Fusion only has the GBA to operate its programming, and due in part to those computing limitations, the promise of the SA-X falls flat— leading instead to a set of mildly tense, obviously scripted encounters that, even in a game this quick and short, feel too few and far between. Still, its big setpiece aside, the B.S.L. station proves a compelling and inspired setting: its discrete environments and biomes contrasting with the omnipresence of the parasites that haunt its every surface, creating a world of deception, illusion, and claustrophobic horror that ranks among the series’ best.

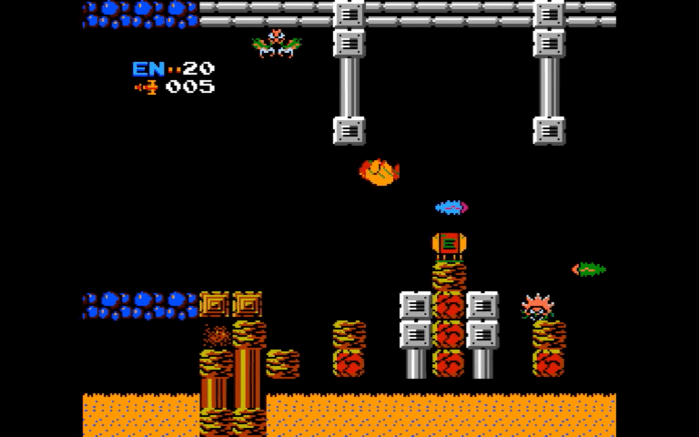

#5: Metroid (NES, 1986)

In a word: frictional. Playing Metroid in the 2020s is an exercise in patience: in understanding and embracing an approach to game design that, outside some small niche spaces, vanished long ago, and in learning to love a kind of friction that modern games rarely ever try to match. That friction is present from the game’s first moment: one designed with the knowledge that the players of the 1980s would assume a character in a platformer should move right, and that instead forced those players left. And it continued in every moment onward — through neon-hued tunnels swarming with hostile, nightmarish creatures and a labyrinth of a world that at times itself seemed like a kind of monster.

In the almost forty years since Metroid was released, games and their players have placed more and more value on a kind of perceived fairness — the fairness people cite when talking about platformers like Celeste or Shovel Knight, in which the game presents its mechanics and obstacles with a kind of perfect clarity. A player should, in one of these games, be able to map and execute a perfect and predictable set of moves, and in doing so would find their way safely past a given hazard. Metroid, on the other hand, takes that ideal of predictability and throws it to the curb. The game delights in a kind of trollish agitation: in tricking its players with invisible chutes above lakes of lava, or with sequences of identical rooms stacked one above the other in a vertical, disorienting maze. It’s this feeling of active malice towards the player — of open hostility towards a “fair” experience — that Zero Mission with its detailed map could never hope to match. It’s also the reason that, once I understood its goals and how to match them, I found this game so strangely, powerfully compelling.

In some ways, Metroid feels like a precursor to the antagonizing worlds of Dark Souls: rife with enemies strategically placed around corners and deadly traps hidden in the floor. The Giants’ Mountaintop Catacombs, a side dungeon placed near the end of Elden Ring, even replicate the labyrinthine feel of some of Metroid‘s most befuddling areas by taking several copies of the same layout of rooms and placing them in sequence with each other. And like the power fantasy that underlies the core appeal of Souls games, Metroid has its own in the form of its progression system — eventually seeing Samus become so powerful that she can blast repeatedly through enemies and chambers without ever even touching the floor. It’s that short but memorable journey — from those feelings of utter aloneness and isolation and that sense of a truly hostile world, to a sense of mastery and power and sheer untouchability — that vaults Metroid above much of what came after it for me, and what keeps it on my mind even with the entirety of the series in its wake.

***

TIER 2 – THE SPIRAL GALAXIES

In the nearly forty years since Metroid came into existence, gaming has seen the birth of countless genres — and over that span, the two games in this tier have demonstrated a rare and lasting kind of immortality. While neither ended up my favorite of the series, their influence over the range and scope of video games was apparent at every turn, and together, they form the singularities at the heart of some of gaming’s vastest galaxies, with innumerable stars and systems held together by their gravity.

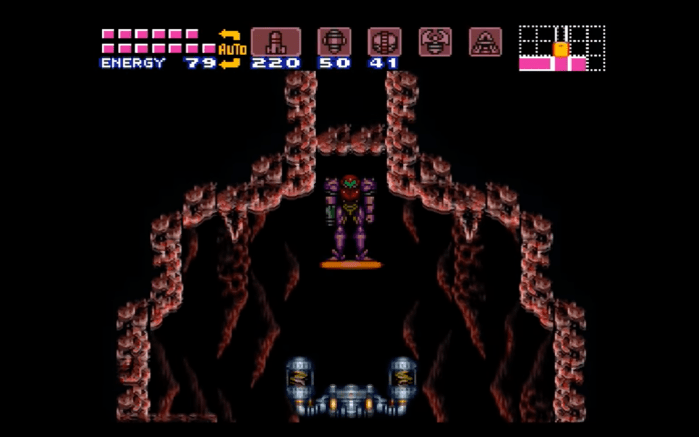

#4: Super Metroid (SNES, 1994)

In a word: haunting. I don’t think I played Super Metroid as much as I communed with it, like visiting a ghost or returning to a forgotten childhood home. Over its near-three decades of existence, the game has barely aged — its mechanics replicated full-sail throughout the genres it inspired, an entire class of games carrying its spirit onward in its wires. Itself a reimagining of the first game’s labyrinthine world, Super Metroid forms the template for the series’ later entires — with the addition of an in-game map as well as several longtime upgrades and abilities. Yet still it develops out the first game’s air of inscrutability and mystery, hiding obtuse secrets and interactions behind creative tricks and puzzles and vastly expanding the breadth and scope of that game’s more compact world. As far as Metroid games, its skeleton forms the foundation for everything that follows, and it remains among the best the series has to offer. As for metroidvanias at large, it stands as a high-water mark, rarely matched and almost never eclipsed, still revolving at the genre’s heart.

Yet Super Metroid‘s influence persists well beyond the boundaries of the Metroid series, or even the genre to which it lent its name. Its eerie, haunting atmosphere and at-times oppressive sense of dread plays as a chilling prototype for the medium’s approach to horror, and the ways in which it configures its environments as biomes, complete with their own landscapes and ecologies, feels foundational to the world design of modern games. It gave a level-oriented medium a taste of a cohesive, interlocking world, and — in an era where, beyond text-heavy RPGs, video game series revolved more around familiar mechanics than connecting stories — it engaged a real sense of narrative progression, with the events of Metroid II returning to drive its plot. There’s a reason every 2D Metroid game opens with a numbered title card: Fusion being 4, Dread 5, and this one Metroid 3; unlike Mario, Zelda, or gaming’s other early standouts, Metroid set out to tell a long and overarching story about isolation, gender, power, and the interplay between manmade horrors and the harshness of the natural world. In marrying a simple, easily followed plotline with a harsh, imposing world, Super Metroid remains a foundational piece of ludonarrative art: a generative point for the emergence of games as a more complex narrative medium. And with everything in mind, there is only one conclusion I can draw about this game: that, at the time, there had never been anything like it, and that — by virtue of the genres that it spawned, the design philosophies it inspired, and the sheer creativity it sparked throughout the medium — there will probably never be anything quite like it again.

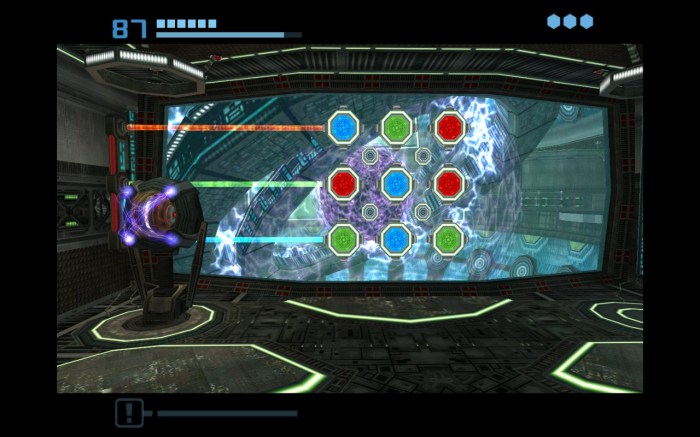

#3: Metroid Prime (Remastered) (GCN, 2002 // Switch, 2023)

In a word: immersive. While Super Metroid‘s ghost flickers through the circuit boards of the genre it inspired, Metroid Prime plays like a kind of missing link. In its effort to translate the gameplay feel and progression of a 2D Metroid game into a 3D space, it brushes up against the design philosophies of 3D Zelda games, configuring its environments and spaces like sprawling dungeons rife with locks and keys, peppering its world with puzzles that all resolve with satisfying jingles. Yet, much in line with the very first Metroid game, its approach to world design — to molding discrete regions into interlocking warrens, complete with backtracking and shortcuts and familiar traps and enemies — feels eerily like a precursor to the world design of Dark Souls, another singularity at the center of a galaxy of games. That the door to its endgame area is visible from its earliest moments feels like the crux of that approach — with pieces of grand importance hidden in plain sight, gaining context only upon the thousandth re-encounter, driving the game’s sense of exploration and discovery.

But despite that foundational approach to world design, Prime‘s greatest strength might just be its soundtrack: a collection of uniquely memorable and widely varied themes that lend ambiance and depth to its diverse range of biomes. Prime dabbles quite often in traditional video game logic: beginning with a forest, then a desert, then a lava world and ice world, but the otherworldliness of its music, the way it marries sci-fi electronica with tinkling piano and echoing percussion, transforms that surface-level roteness into a showcase of aesthetic range. Tracks like the Tallon Overworld and Phendrana Drifts themes drive the game’s momentum, giving their respective areas a sense of atmosphere beyond their simple stereotypes. Likewise, when Prime injects game-y logic into its larger sense of combat — like color-matching enemies with each of Samus’s beams — the sheer smoothness of its feel and the ease of its traversal serve the same function as its music: granting it sublimity, turning what could easily have been the Metroid series’ most outwardly game-y video game into a showcase of immersion, one in which all those disparate elements that make up the fabric of the medium can resonate in perfect harmony.

***

TIER 1 – THE ROGUE STARS

And here we are at last: my sense of Metroid‘s peak, the pair of games that stuck with me from the moment I first played them, and that, for markedly different reasons, have remained on my mind ever since I put them down. All stars are born from nebulas and most exist in galaxies, but a few — the rogue, or intergalactic stars — make their own way out into the emptiness of space. Both these games took the foundations laid by the series’ galactic hearts and built something irrepresibly their own: one sometimes barely recognizable as a Metroid game at all, the other a breakneck celebration of the series at its finest.

#2: Metroid Prime 3: Corruption (Wii, 2007)

In a word: exhilirating. Corruption was this project’s big surprise, the game I expected to land around the middle of this list and that yet, by its scope and sense of joy, found its way nearly to the top. At times, it barely resembles most of what the Metroid series has to offer, with side characters and cutscenes and a world split between several different planets, with Samus’s ship as its only interconnective tissue. It wears influences from Half-Life and Star Wars on its sleeve, casting Samus as a silent protagonist in an intergalactic war, even replicating the cloudbound vistas and steampunk-themed milieu of the latter’s famed Cloud City. And yet, when the time comes for the game to deliver some understated interstellar horror, it comes up with one of the series’ eeriest, most chilling settings — showcasing a kind of range that nothing else in Metroid can even hope to match.

It’s that sense of range that powers every moment of Corruption: the way its settings drift from the steely Noiron forest to Bryyo’s fiery jungle; from Elysia’s skybound city to the Pirate Homeworld’s technofascist nightmare. It’s in the way its battles pit Samus against both compatriots and enemies — everyone from fellow bounty hunters to Ridley’s final form — and the way its soundtrack drifts from mournful to climactic and everywhere in between. It frames Samus’s expanding power as a disease gnawing at her bones: a clump of cancerous Phazon metastatizing in her heart, growing stronger with each radioactive upgrade that she finds. And yet, amid the noise and warfare, it still finds room for what I found to be the series’ most haunting setpiece: the abandoned, haunted hallways of the GFS Valhalla, where the series’ trademark doorways often open to the sight of corpses dissolving into ash.

With those points in mind, I understand why Corruption rarely ranks this highly for most fans of the series. In many ways, it jettisons the traditional Metroid structure — with its interlocking world, its sense of loneliness and horror — in favor of something on the surface louder, brighter, more bombastic. For me, it might be a function of this project, of playing all these games in (relatively) quick succession that saw me gravitate so strongly towards the series’ most idiosyncratic entry. But when I think about Metroid‘s most memorable moments, I think about those quiet trips around that haunting station, the red nebulas outside its windows, the bodies blocking doorways, crumbling into dust. I think about riding zip-lines around SkyTown, surging through a world above the clouds. I think about the hostile architecture of the Pirate Homeworld, devastated by pollution, its sky endlessly disgorging acid rain. I think about the battles with Rundas, Ghor, Gandrayda — melancholic yet exhilirating, narratively and mechanically among the series’ best — and the final descent into Phaaze, the living planet, twisted and warped in ways only the first game’s Impact Crater even tried to match. None of those experiences are alien to Metroid; they just approach its horror from new and varied angles, experimenting with a wider language pulled from elsewhere in the genre. In combination, they give the series one of its brightest stars: a game unafraid to take risks and reach for new ideas, even if it has to reimagine the core tenets of the series along the way.

#1: Metroid Dread (Switch, 2021)

In a word: sublime. Over the forty years and fifteen games represented on this list, Metroid has taken on a wealth of different forms. It’s seen environmental puzzlers and kinetic action-platformers alongside a pinball adaptation and a weighty deathmatch shooter. It’s tested out myriad control schemes, from the DS and 3DS’s touchscreens to the Wii’s motion possibilities. It’s shaped the way games as a medium construct, catalog, and understand both 2D and 3D spaces, and in doing so it’s practiced different ways of translating between them. It’s spawned some of the modern scene’s most popular subgenres, and seen itself reinvented along the way.

In a way, it’s fitting then that Metroid Dread — the series’ newest entry, and its triumphant return after a sojourn in the desert — ended up my favorite of the bunch. From books to albums, TV shows to games, serial art tends to lose itself to time, with rough edges ground away by iteration after iteration until only a hollow sort of polish still remains. But while Dread is polished to a mirror shine, it also feels celebratory: a commemoration of everything that Metroid ever was and a beacon showing everything it could still be. With its origins in the 8-bit era, Metroid found its early sense of isolation in the limitations of its infrastructure: the necessary darkness and abstractions of those late-80s, early-90s consoles. With the sharper fidelity that followed, it’s struggled to rediscover that sense of interstellar loneliness — drifting instead into the business of games like Fusion, Other M, and the later Primes. But Dread, in the way it makes use of its 2.5D perspective, finds a way to marry modern clarity with that sense of hidden horrors. There’s a whole world happening in its backgrounds: creatures lurking, machines rumbling, veiled and hostile soldiers constructing savage monsters. Combine that with the stalking presence of the E.M.M.I. — the true realization of Fusion‘s SA-X — and Dread, despite its bright lights and sparkling scenery, comes the closest to the series’ atmospheric goals than anything since Super really has. And along the way, it takes in pieces from every other era — the early 2D entries’ kinetic platforming and love of restless motion; Prime‘s environmental puzzles and responsive, shifting world; Fusion‘s antagonizing computer and Samus Returns‘s Aeion gauges and abilities — and combines them into something that, unlike MercurySteam’s first flawed attempt at Metroid, plays with a responsiveness and feel above and beyond the sum of its substantial parts. Dread may first and foremost be an action game, absent some of the exploratory genes that characterized the series at its best, but it’s one of the best damn action games ever made: a tense, ferocious, and utterly sublime capstone for one of gaming’s most venerable series.