Something I've always enjoyed in my time writing critically on media are weird comparisons — taking two pieces of media that otherwise would never be placed alongside each other and seeing how hard I have to smash them together to generate something interesting. In that vein, I recently finished binging Dexter, and made a joke with a friend who also loves Disco Elysium about whether Dexter Morgan had access to Shivers. Then I thought about it a little too long... and this happened.

Category: Writing

To the Stars and Back: A Metroid Series Ranking

Strap in for my tiered ranking of every Metroid game — from the ones I struggled to make it through to the ones I wish I could experience for the first time over and over again.

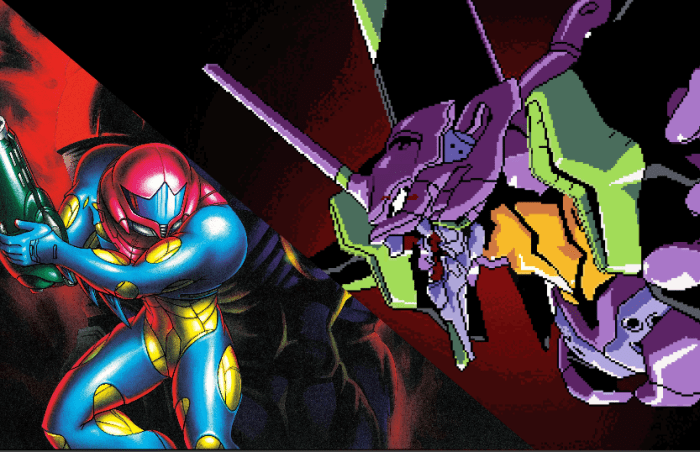

Screw Attacks, Third Impacts, and Other Interstellar Horrors

As a medium, video games are defined by different forms of touch. Both the interface between player and game and the action of most games itself relies upon a set of simple rules — what kinds of responses a particular touch will engender, and what groups of pixels can and cannot be safely touched. Games have their own language for these interactions: collision detection defines the act of in-game touch, and hitboxes measure where and when that touch brings pain. In most games, this becomes a kind of broad and neutral framework: a foundation on which mechanical and narrative structures can be built. But in Metroid, touch becomes its own singular kind of horror.

In Abandoning Perfection, Rain World Finds Nirvana

Rain World has a certain reputation in the gaming sphere: a hellishly difficult 2D platformer largely panned by critics at release, but that found a second life via a relatively small and deeply dedicated community of fans. I had tried to play it several times over the past few years, emboldened each time by various accomplishments in other "difficult" games — and each time I found myself unable to make it past the first few levels. This time, I broke through with the help and advice of some friends on the Waypoint forums, and behind that initial wall I found a piece of art that, especially in its "remixed" form, has more to say about that idea of video game difficulty than any other game I've played.

Marvel’s Spider-Man and the Allure of the Carceral State

Superhero comics, as it is, are usually a far more complex medium than their adaptations let on. But as with Spider-Man, comics are typically at their best when their focus narrows and becomes more intimate — when writers focus on characters and their relationships, and on the idea that these are real people behind their costumes and masks. At its best, that's exactly what Spider-Man does; it feels like a comic book not just in its action, movement, and sound design, but in the way it approaches its heroes and villains.

It's just a shame that, in the end, it also insisted on being so unfailingly, unflinchingly, a Video Game.

Black Lives Matter | Another World is Possible

If you are one of those visitors, happen upon this post, and, like me, believe that the current order is brutal, unjust, and fundamentally broken—please understand that this is not the way things have to be.

Another world is possible.

You Might Have Missed: The Get Out Kids

It all feels like The Get Out Kids intended itself to be a fairy tale. Or at least, it mashes a fairy tale ending onto the skeleton of Pennywise the Dancing Clown, without ever quite checking to make sure the two had fit together. It at once wants to be a grim, spooky horror story, a lonely fable about a pair of outcast kids, and a fairy tale about found family. But—in the same way it never quite commits to a clear point-of-view for its player—it never quite ends up being any of those things either.

Myles Garrett, Football’s Hypocrisy, and the Absurdity of “Consensual” Violence

Myles Garrett's violence created a flashpoint for that mindset—it evoked the reaction that it did because, in a game where multiple players were taken off the field with more damage to their skulls and brains than Mason Rudolph received from Garrett's helmet-slam, it revealed just how transparent that line of thinking really was. It revealed complicity and, in doing so, a wash of cognitive dissonance from everyone from nameless twitter eggs to Adam fucking Schefter himself. It revealed the sheer absurdity of football, starkly and plainly, and people just couldn't handle that.

In Outer Wilds, They Blew Up the Sun, and There Was Nothing We Could Do

Outer Wilds is infused with a lingering tinge of melancholy, coupled with an overwhelming sense of smallness... All of these systems operate like clockwork, unfazed by your minuscule intrusions. In much the same way the Sun will never respond to your pleas. As you uncover the story of the Nomai, you learn—through implication and observation, through long-forgotten writings and the broken remains of their stations—that because of a lack of foresight and one too many human mistakes, there is no way to stop the progress they tried and, in their time, seemingly failed to set in motion. Millions of years later, their machines blew up your sun. And there's nothing you can do to stop it.

On the Creeping Horror of Salt and Sanctuary, and its Island of Twisted Reflections

In doing so, Salt & Sanctuary builds one of the most rewarding final acts I've experienced in a video game, that translates an atmosphere of mounting dread into a sequence of sudden, heightened horror, and then, in its final moments, a rush of catharsis.